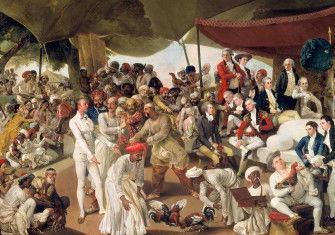

British Explorers and Orientalists in India

During the 18th and 19th centuries, cultural curiosity and orientalism inspired generations of British imperialists to unearth India’s past.

For a generation brought up on Edward Said’s writings on Orientalism, it may come as a surprise that it was British Orientalists who rediscovered India’s history and artistic heritage and made it accessible to all. The Palestinian-American Said knew little about India or else he might have recognised the cultural curiosity that inspired thousands of Britons to explore India’s past.

The ‘colonial gaze’, which Said’s followers dismiss as colonial appropriation, took the form of paintings and engravings by artists such as Thomas Daniel and William Hodges, long before Britain acquired any imperial ambitions in India.

Then there was Sir William Jones, the polymath who contributed more than any other individual to India’s national renaissance. Alongside his day job as a judge in Calcutta (now Kolkata), the East India Company’s capital, Jones studied and mastered Sanskrit, translated its classic texts and used the language to unlock the glories of India’s long-forgotten Hindu and Buddhist past.