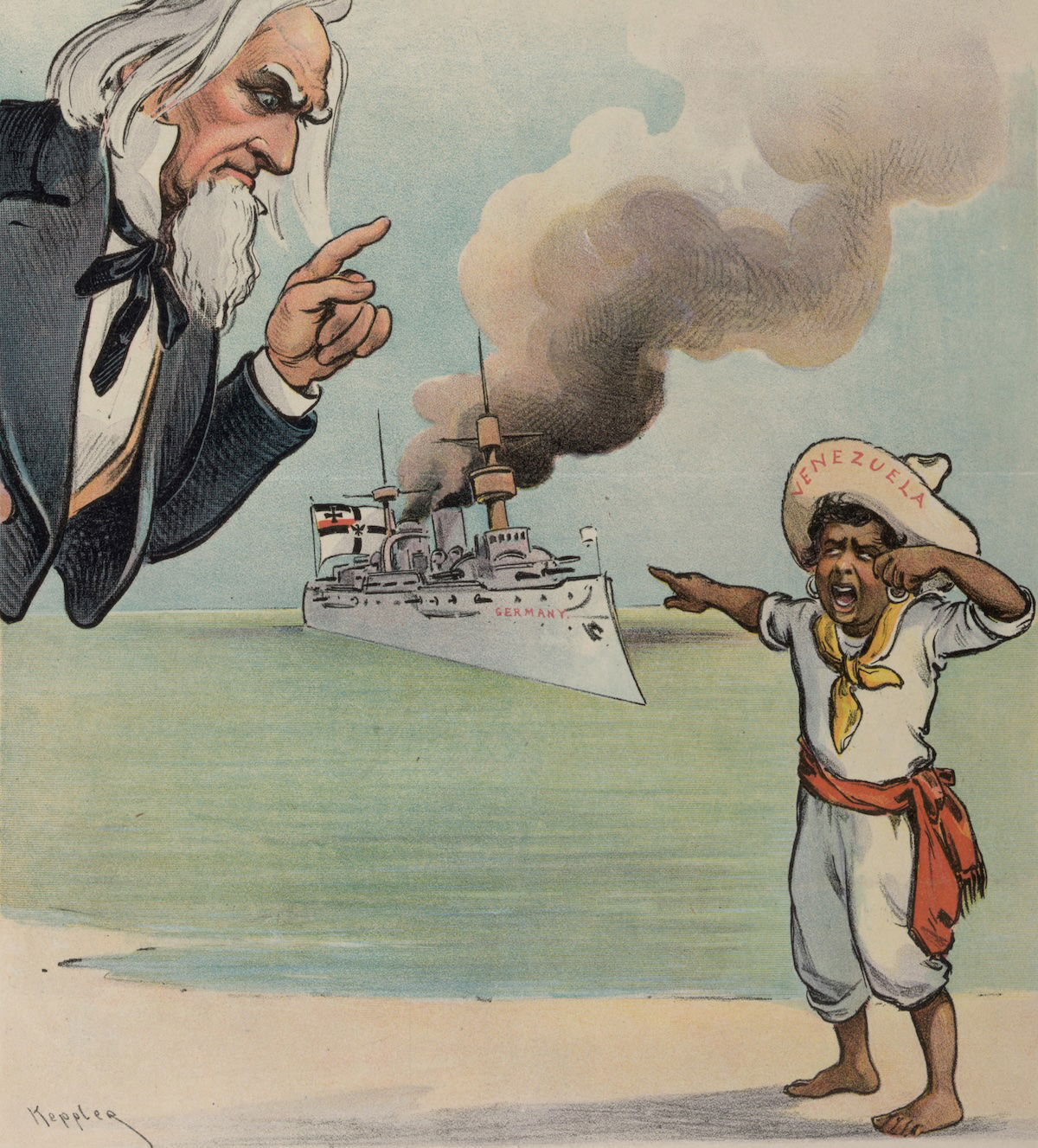

The 1902 Blockade of Venezuela

In 1902 a revolutionary dictator named Castro provoked an unlikely Anglo-German naval demonstration off the coast of Venezuela.

Looking back 60 years later at the brief episode in the winter of 1902-3, when three Powers blockaded the coast of Venezuela and seven others then joined them in insisting on a settlement of their claims, one is struck by the transformation that has come over the relations between the countries now called “developing” and those called “donor.”

At the beginning of this century, no major Powers were interested in providing technical assistance to a less highly evolved state; what they were interested in was to ensure that their nationals, traders and concessionaries were not molested in their legitimate efforts to make their living and, in the process, siphon off a share of the wealth of the country. The benefit, often immense, that was derived by the less developed country was a by-product.

At the turn of the century, Venezuela was still one of the poorer countries of Latin America. Ever since the 16th century Europeans had believed that “El Dorado” lay in this part of the continent; but none had fully grasped that it was “the black gold” that was to make Venezuela wealthy.