What was the Congress of Vienna?

Stella Ghervas examines the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the Great Powers’ attempt to create a new European order following the defeat of Napoleon.

The ‘long 19th century’ was a period of relative peace that began arguably with the Congress of Vienna in September 1814 and lasted until the outbreak of the First World War in July 1914.

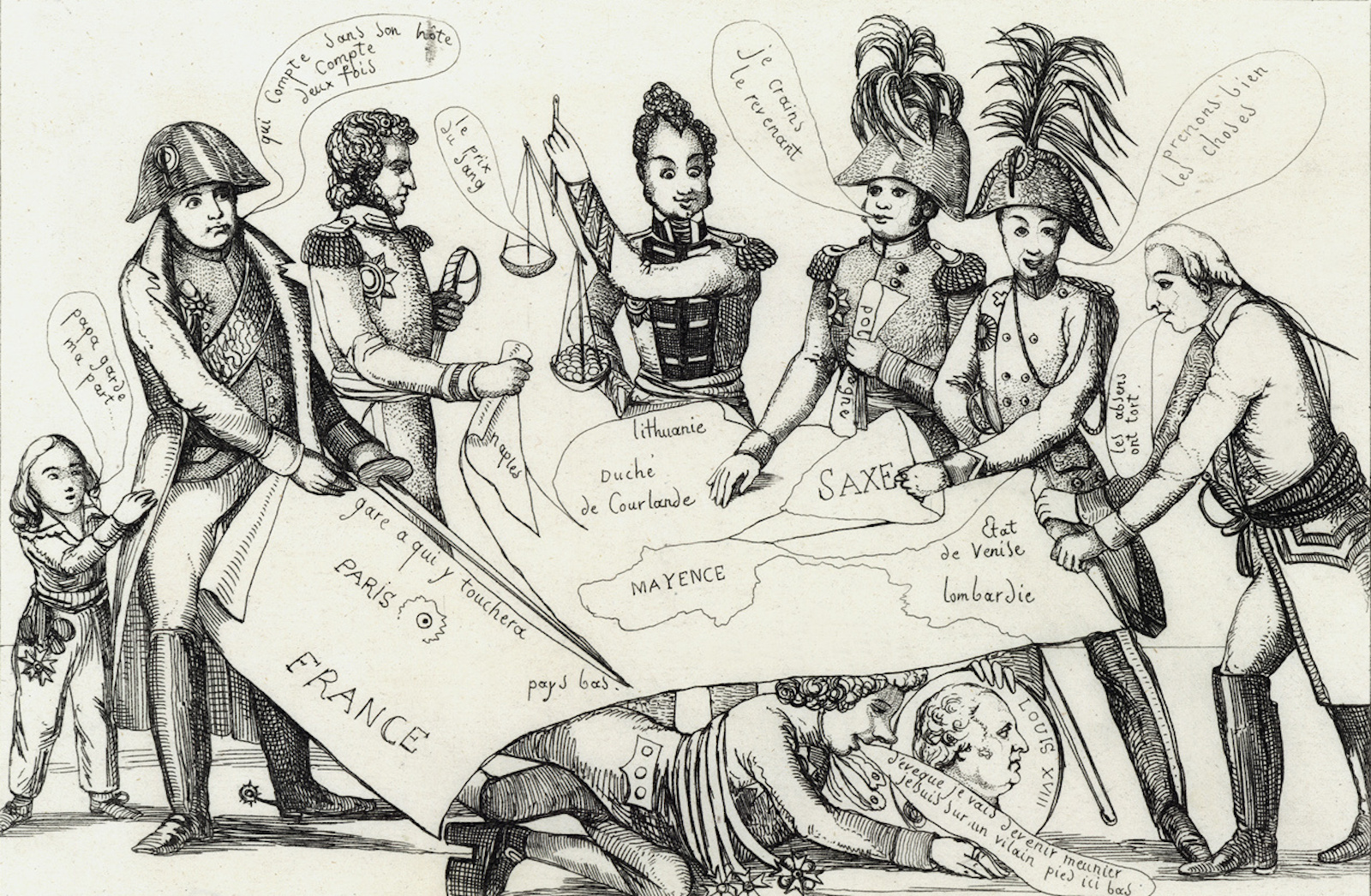

Emperor Napoleon was defeated in May 1814 and Cossacks marched along the Champs-Elysées into Paris. The victorious Great Powers (Russia, Great Britain, Austria and Prussia) invited the other states of Europe to send plenipotentiaries to Vienna for a peace conference. At the end of the summer, emperors, kings, princes, ministers and representatives converged on the Austrian capital, crowding the walled city. The first priority of the Congress of Vienna was to deal with territorial issues: a new configuration of German states, the reorganisation of central Europe, the borders of central Italy and territorial transfers in Scandinavia. Though the allies came close to blows over the partition of Poland, by February 1815 they had averted a new war thanks to a series of adroit compromises. There had been other pressing matters to settle: the rights of German Jews, the abolition of the slave trade and navigation on European rivers, not to mention the restoration of the Bourbon royal family in France, Spain and Naples, the constitution of Switzerland, issues of diplomatic precedence and, last but not least, the foundation of a new German confederation to replace the defunct Holy Roman Empire.

In March 1815, in the midst of all these feverish negotiations, the unthinkable happened: Napoleon escaped from his place of exile on Elba and re-occupied the throne of France, starting the adventure known as the Hundred Days. The allies banded together once again and defeated him decisively at Waterloo on June 18th, 1815, nine days after having signed the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna. To prevent France from ever again becoming a threat to Europe, they briefly entertained the idea of dismembering it, just as they had Poland a few decades earlier. In the end, however, the French got away with a foreign military occupation and heavy war reparations. Napoleon was shipped to St Helena, a forlorn British possession in the South Atlantic, where he stayed out of mischief until his death.

Settling the consequences of the war was difficult enough, but the Great Powers had a broader agenda: creating a new political system in Europe. The previous one had been established a century earlier, in 1713, at the Peace of Utrecht. Based on the principle of the balance of power, it required two opposing military alliances (initially led respectively by France and Austria). By contrast, the victors over Napoleon aimed for a ‘System of Peace’: there was to be only one political bloc of powers in Europe. This led to the creation of a cycle of regular multilateral conferences in various European cities, the so-called Congress System, which functioned at least from 1815 to 1822. It was the first attempt in history to build a peaceful Continental order based on the active co-operation of major states.

From Utrecht to Vienna

Why did the participants at Vienna want to reform the Utrecht system? Why had active cooperation become so necessary in 1814 and not before? The explanation is rather obvious: the previous equilibrium was broken. During the 18th century the military strengths had been evenly divided between the two major alliances, but Napoleon had tipped the scales. With a powerful army, he had managed to crush all his opponents except Britain and Russia, creating a continental empire. Defeating him had required a massive joint effort from the other powers. The turning point was the battle of Leipzig in October 1813, in which more than half a million soldiers took part.

Worse still, the Napoleonic wars had shattered borders and broken political institutions in several parts of the Continent, especially in Germany. In order to heal its wounds, Europe needed peace. Hence the first priority was to preserve it from two of its chronic problems: hegemonic adventures (so there would never again be a Napoleonic empire) and internecine wars (so there would be no reasons to fight each other).

Interestingly, the Congress System was the combination of distinct antidotes proposed by the Great Powers. The British Cabinet and its diplomats, led by Viscount Castlereagh, still believed in its earlier formula, ‘the balance of power’. Traditionally, British strategy had been anti-hegemonic and forward-looking. At Vienna, just as at Utrecht a century before, Britain considered it essential to contain France against a possible military resurgence. Indeed, in 1815, Britain supported a similar scenario of buffer states around France as it had done in 1713, comprised, north to south, of the Dutch kingdom, Switzerland and Savoy. The British went a little further this time: they wanted a new European order that was sympathetic to their own interests, which were mostly about sea trade. If that could be obtained by parley, rather than by military competition, so much the better – and within those limits, Britain would be willing to maintain frequent diplomatic relations with the other European powers. Indeed, its envoys actively participated in the Congress System in the years to follow.

As for Austria, Prince Klemens von Metternich also relied on a form of ‘balance of power’, though his application was more down-to-earth. In 1813, when the victorious Russian army marched into Germany and liberated Berlin, joining a coalition against France had become a life or death proposition for Austria. It thus joined in the battle of Leipzig and the following campaigns. After Napoleon was defeated Austria had a further thorny issue to solve: how to manage its powerful and burdensome Russian ally? It had no option other than to go along with Russia and to enter into a ‘balance of negotiation’, playing off the allies of the same bloc against each other.

Surprisingly, the Russian view on peace in Europe proved by far the most elaborate. Three months after the final act of the Congress, Tsar Alexander proposed a treaty to his partners, the Holy Alliance. This short and unusual document, with Christian overtones, was signed in Paris on September 1815 by the monarchs of Austria, Prussia and Russia. There is a polarised interpretation, especially in France, that the ‘Holy Alliance’ (in a broad sense) had only been a regression, both social and political. Castlereagh joked that it was a ‘piece of sublime mysticism and nonsense’, even though he recommended Britain to undersign it. Correctly interpreting this document is key to understanding the European order after 1815.

While there was undoubtedly a mystical air to the zeitgeist, we should not stop at the religious resonances of the treaty of the Holy Alliance, because it also contained some realpolitik. The three signatory monarchs (the tsar of Russia, the emperor of Austria and the king of Prussia) were putting their respective Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant faiths on an equal footing. This was nothing short of a backstage revolution, since they relieved de facto the pope from his political role of arbiter of the Continent, which he had held since the Middle Ages. It is thus ironic that the ‘religious’ treaty of the Holy Alliance liberated European politics from ecclesiastical influence, making it a founding act of the secular era of ‘international relations’.

There was, furthermore, a second twist to the idea of ‘Christian’ Europe. Since the sultan of the Ottoman Empire was a Muslim, the tsar could conveniently have it both ways: either he could consider the sultan as a legitimate monarch and be his friend; or else think of him as a non-Christian and become his enemy. As a matter of course, Russia still had territorial ambitions south, in the direction of Constantinople. In this ambiguity lies the prelude to the Eastern Question, the struggle between the Great Powers over the fate of the Ottoman Empire (the ‘sick man of Europe’), as well as the control of the straits connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Much to his credit, Tsar Alexander did not profit from that ambiguity, but his brother and successor Nicholas soon started a new Russo-Turkish war (1828-29).

Astonishingly, the Holy Alliance was also imbued with an idea inspired by the Enlightenment: that of perpetual peace. A French abbot, Saint-Pierre, had published a book in 1713 (the same year as the Peace of Utrecht), where he criticised the balance of power as being merely an armed truce. By contrast, he proposed that European states should co-exist, while retaining their freedom, within a federation, complete with a court and a common army. The Holy Alliance certainly came short of that purpose, since it was merely a declaration of intentions. It was nevertheless a multilateral compact, not for making peace in Europe, but for maintaining peace among sovereign European states. Eventually, most of them, with the exception of Britain and the Holy See, signed the Holy Alliance.

Appointed by Providence

Alexander had been a man of fairly liberal disposition, as far as Russia was concerned. He had appointed a Polish patriot, Adam Czartoryski, as his chef de cabinet from 1804 to 1806, had upheld the parliamentary system of Finland, granted a constitution to Poland in 1815 and later supported a constitutional monarchy in France. However, the Holy Alliance and the Congress System that followed degenerated into what is termed the ‘Reaction’, as the formerly threatened European aristocracies concentrated power and wealth back into their own hands.

The cause can again be found in the Holy Alliance, since it stated that the three contracting monarchs were appointed by Providence; in other words, that they had divine legitimacy. It thus reaffirmed the traditional top-down view of society, where power stemmed from God to the people and not from the people to their sovereign. In practice, the monarchs refused to answer the increasing demands for political representation by the cultured elites. This proved ill advised, since the latter started voicing critical opinions in the press and parliaments. Failing to be heard, protesters took to the streets, as in student riots in Germany in 1817. The first ‘reaction’ on the part of the Great Powers was to silence parliaments and censor the press. Italy also ignited with popular uprisings and further troubles in Spain spilled over to Mexico and South America.

To make things worse, the monarchs soon started borrowing each other’s armies to put down rebellions. Since the term ‘peace’ had also, at the time, a connotation of ‘law and order’, it was justifiable under the Holy Alliance. ‘Peace’ became synonymous with repression of popular discontent. In 1830 Czartoryski, who found himself on the wrong side of a Polish rebellion against Russia, lamented that even though perpetual peace had become the conception of the most powerful monarchs of the Continent (he referred in particular to Tsar Alexander), diplomacy had corrupted it and turned it into venom. The Congress System rapidly became a directorial system: a syndicate of monarchs who supported each other against internal political competitors, especially their parliaments.

Outward success, internal failure

How effective was this ‘system of peace’? This is part of the age-old debate between ‘pacifists’ and ‘securitarians’, the former believing that peace leads to security, the latter considering that security should be the sine qua non for peace (‘if you want peace, prepare for war’).

The political doctrine applied by Tsar Alexander in the post-Napoleonic era was definitely pacifist. In that case, however, pacifism was not meekness. In 1815 the tsar had not only won the Great Patriotic War against Napoleon in Russia. His army, by far the most powerful in Europe, had marched into the heart of Europe to liberate both Prussia and Austria. Having little left to prove, he could afford to champion peace, including being seen to do so in the eyes of his own subjects. In this respect, he rather applied the principle that ‘peace is for the strong and war is for the weak’. In terms of international relations, the doctrine of the Great Powers was a resounding success, but in terms of internal policy, it was an unmitigated failure.

The Congress System formally ended in 1823, when the Great Powers stopped meeting regularly. Yet the one-bloc system went on for three decades. It survived the wave of European-wide revolutions of 1848, when the monarchs of Austria, Prussia and Russia duly assisted each other to crush the insurgents. The entente between the great powers finally broke down only five years later. In 1853 Russia decided to go for the jugular of the Ottoman Empire and threatened Constantinople. Britain and France countered by sending an expeditionary force, starting the Crimean War. The root of the crisis could, again, be found in a flaw of the Congress System (and again in the Holy Alliance): the omission of the Ottoman Empire from the European peace. The Concert of Europe endured until 1914, but the dream of perpetual peace in Europe died at the siege of Sevastopol (1854-55), during the Crimean War.