‘Man-Devil’ by John J. Callanan review

Man-Devil: The Mind and Times of Bernard Mandeville, the Wickedest Man in Europe by John J. Callanan revels in the making of the controversial satirist and philosopher.

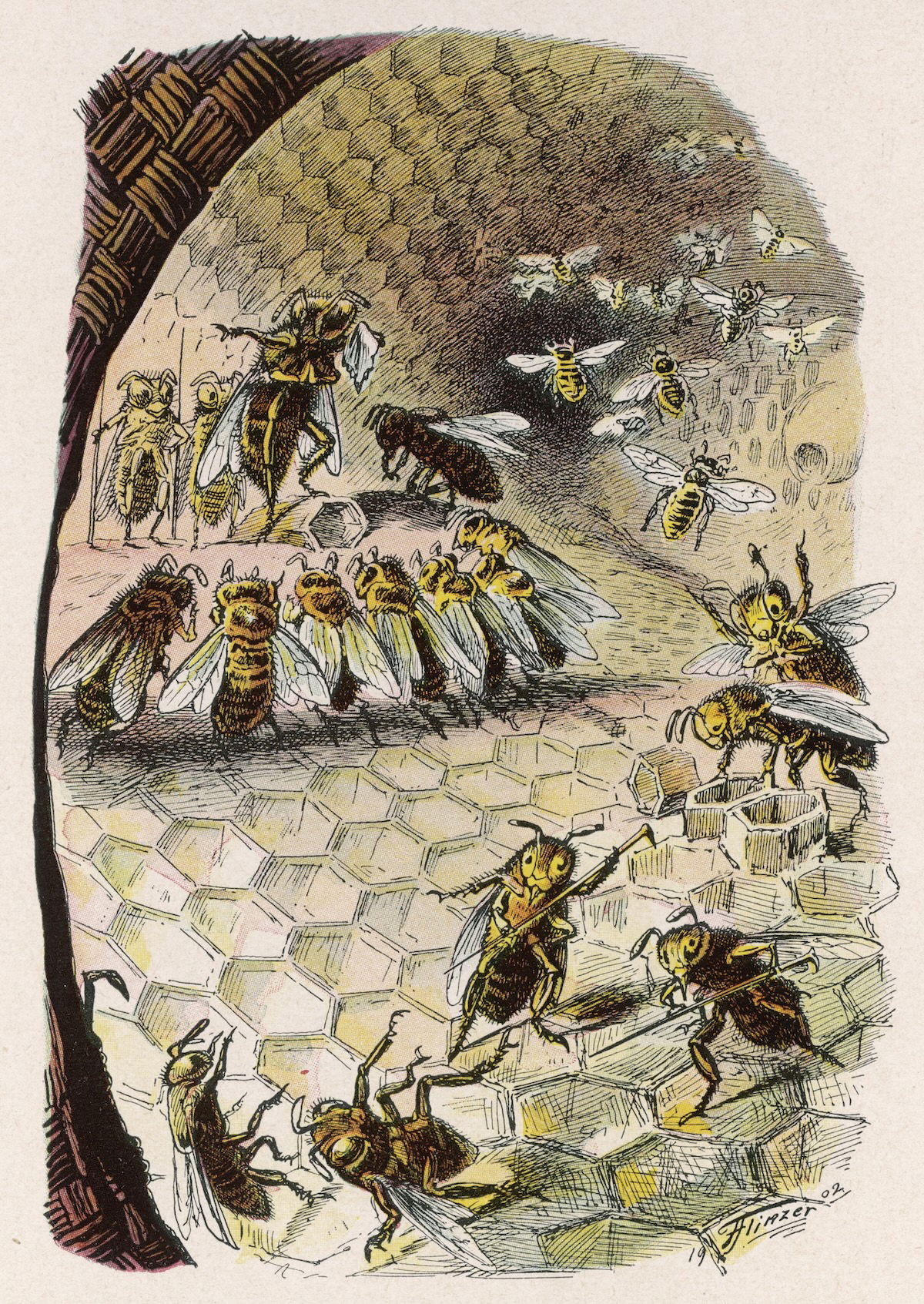

Imagine a beehive. The inhabitants are nasty little things: venal, selfish, and corrupt; greedily buzzing around guzzling honey and flaunting their stripes. Even so, the hive prospers. Then, one day, by a sudden act of God, the bees clean up their act. They become virtuous. And before they know it, the hive is in free-fall. Without vanity, there is no need for fashionable clothing. Without pride or luxury, the construction industry falls apart. Without gluttony or boozing, chefs and vintners are out on their feet. Without crime, the police twiddle their thumbs. And without fraud and deception, the lawyer-bees (we’re really stretching the metaphor here) are put out of business: who needs contract law when everyone is so damned honest? Now set that story to wince-inducing doggerel, add some explanatory notes and an introductory essay, and you have yourself The Fable of the Bees, Bernard Mandeville’s shock-success of 1714.

Born in 1670 to a family of wealthy Dutch physicians, Mandeville received his medical training in the Netherlands before establishing his own practice in London in his 20s. It was an unlikely background for a social and political theorist, but an advantageous one. As John Callanan shows in his entertaining and enlightening new book, Mandeville’s background as a physician instilled in him the sense that one could not comprehend the fundamental mechanics of society without first grappling with what made humans human. To understand the hive, you needed to understand the bee. For this reason, Mandeville devoted just as much time and effort to investigating matters such as hypochondria and sex as he did to sociological analysis. All these things were connected. Society was shaped by human behaviour and human behaviour was governed by base animal instinct. While this insight had, to an extent, been anticipated by theorists such as Thomas Hobbes, Mandeville’s capacity to link human psychology with broader socio-economic patterns was genuinely and radically new, anticipating the modern field of behavioural economics by nearly three centuries and the ideas of Adam Smith by a generation.

The moral of Mandeville’s fable is obvious enough: a stable and prosperous commercial society relies on a degree of behind-the-scenes rule-twisting and competitive high jinks. The notion that greed might be good is perhaps not so offensive in this age of economic liberalism, but it was deeply shocking at the time. The backlash was extreme. He was, according to his enemies, a ‘Man-devil’ sent from hell, worse even than the notoriously unprincipled Machiavelli. Not until the middle of the 18th century, long after Mandeville’s death, was he taken seriously as a thinker on society, economics, and human nature.

Although critics found plenty to denounce in the substance of The Fable of the Bees, the book’s style gave equal offence. Mandeville made his arguments not with the muscular quasi-scientific reasoning of Bayle or Hobbes, but rather in prose that is teasing, scandalous, and often laugh-out-loud funny. For instance, when Mandeville argues that ‘vice proceeds from the same origin in men, as it does in horses’, he is making a serious claim. Just as the most energetic of stallions might be strapped to a cart and put to work, so we should harness the fundamental qualities of human nature for the greater good of society; to try and quash the essence of what makes us human (or what makes a horse a horse) would be futile. At the same time, though, there is something deeply outrageous in the comparison of human beings to horses. Jonathan Swift would make hay with the same idea in Gulliver’s Travels (1726), where the equine Houyhnhnms are the embodiment of chilly rationality while the humanoid Yahoos represent the depravity of mankind.

More shocking still was Mandeville’s willingness – indeed, enthusiasm – to dispense with the entire framework of morality and virtue. You wouldn’t expect horses to behave according to an externally imposed moral compass – why should humans be any different? As Callanan summarises it: ‘Moral virtue itself was a con, an invention of politicians to keep the herd of society adequately docile.’ Reissuing the Fable in 1723, Mandeville added new essays attacking the priggish stoicism of ‘Cato’, the nom de plume of the Whig pamphleteers John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, and, with typical contrarian flair, charity schools. Callanan marshals the evidence superbly and demonstrates that this line of thought was entirely in keeping with the broader Mandevillian project: ‘It is requisite that great numbers should be ignorant as well as poor. Knowledge both enlarges and multiplies our desires, and the fewer things a man wishes for, the more easily his necessities may be supplied.’ And yet, reading these essays, one cannot shake the feeling of being taken for a ride. It is the sort of statement that one might expect from Swift’s modest proposer, with his scheme for selling the children of the Irish poor for meat. As ever with Mandeville, he states absurdities with a straight face while parroting stale moral pieties with a wink and a nudge.

I suspect it is Mandeville’s combination of caustic prose with penetrating sociological and psychological analysis that makes him so difficult to place. He is one of those rare figures who you are just as likely to encounter in an undergraduate seminar on the history of ideas as on a degree in English literature. He is both a philosopher and a satirist. Disentangling the one from the other is like trying to separate a stiff gin and tonic into its component parts. Callanan is no fool and, unlike some of his predecessors in the field of Mandeville studies, his ear is finely tuned to his subject’s sense of humour. He gets it. Perhaps the broader lesson of this superb book is that satire, when properly done, should not be a matter of sinking giggling into the sea, but of diagnosing, like a physician, the fundamental disease of mankind. It can be – should be – profound, thought-provoking, a spur to action. Mandeville was a dire poet but, by that criterion, an excellent satirist.

-

Man-Devil: The Mind and Times of Bernard Mandeville, the Wickedest Man in Europe

John J. Callanan

Princeton University Press, 328pp, £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Joseph Hone is author of The Paper Chase: The Printer, the Spymaster, and the Hunt for the Rebel Pamphleteers (Chatto & Windus, 2024).