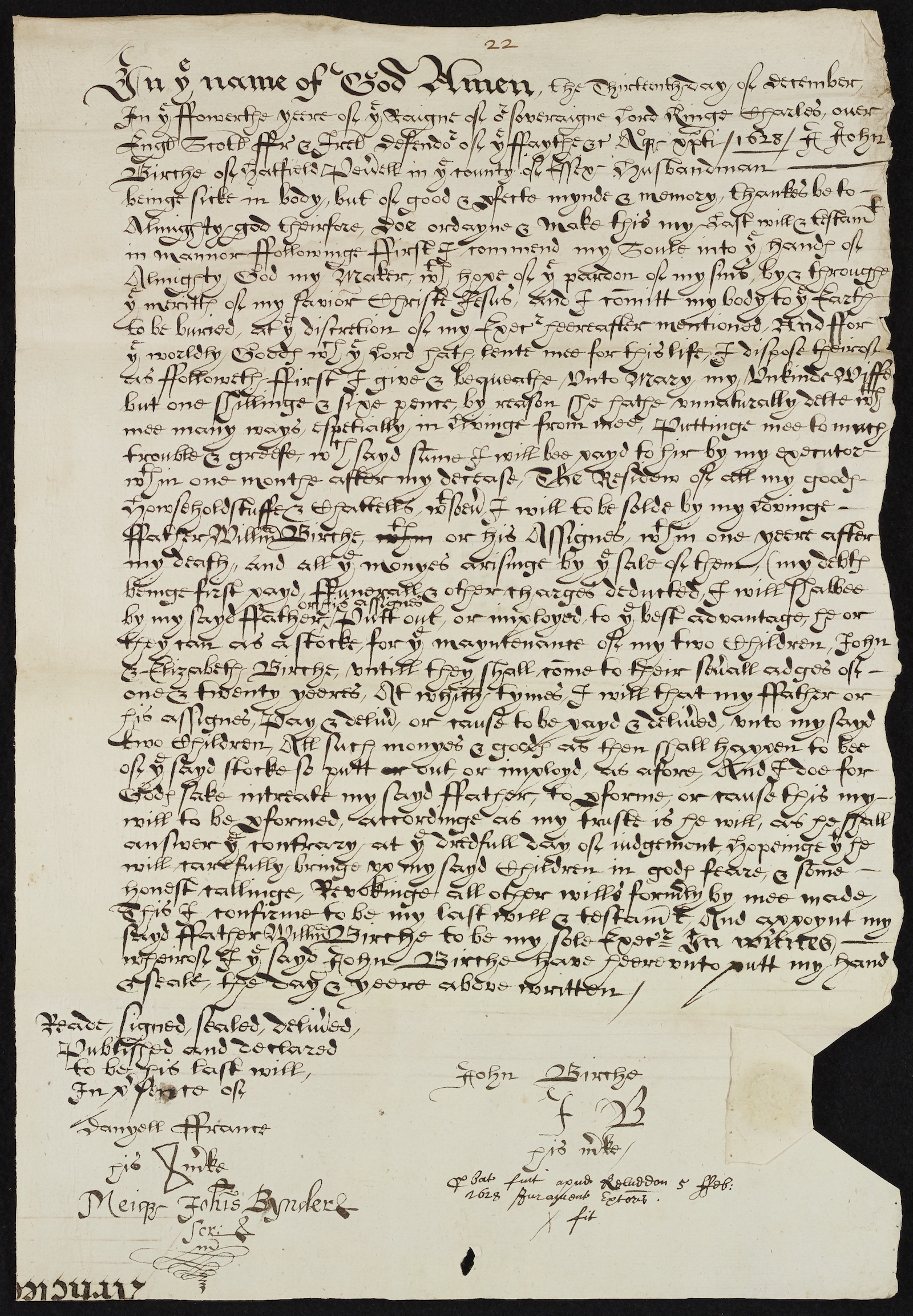

The Value of Wills to Historians

Wills in early modern England tell us much more than simply who left what to whom, and should not be discarded lightly.

A last will and testament does not, in and of itself, possess the value of, say, the family silver. But it is a vital document for all involved: the testator and the legatees, but also, later, for the historian. Where inventories can be more detailed in their lists of possessions made shortly after an individual’s death, the will is where kinship networks, friendships and care are found amid the stuff of the bequests. Wills reveal to us what the people of the past held dear and offer a glimpse of lives that might otherwise be lost. And we should not assume that the conventional nature of the document means that it is not also a place where individual lives might shine through. Indeed, it could be argued that this adherence to conventions highlights the distinctiveness of some testators’ choices and words.