Meet you There

Crossroads: meeting places or religious locations plagued by devils and demons?

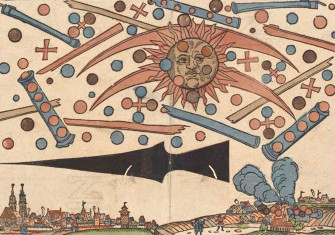

Like most towns, the place where I grew up has a recognisable crossroads at its centre. Strikingly, the west-east thoroughfare is split by one of the largest churches in the area. As Bill Angus’ new study demonstrates, this is unlikely to be a coincidence. Crossroads have practical purposes, allowing the confluence of ways. But they also have a symbolic importance in many cultures as meeting places and sites of parting, religious locations plagued by devils and demons where one could just as easily meet a coven of witches as happen upon redemption bestowed by a preternatural being.

Angus’ book, like any crossroads, offers a variety of possible paths. An early chapter on musical history is a case in point. The devil at the crossroads is a recurrent motif in blues music: the great African American guitarist Robert Johnson was said to have entered a Faustian pact with the devil at the point where Highways 49 and 61 meet in Clarksdale, Mississippi, exchanging his soul for his supreme musicianship sometime in the early 1930s. Recorded in 1936, his song ‘Crossroad Blues’ offers a tantalising glimpse of the encounter:

I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees

Asked the Lord above, ‘Have mercy, now, save poor Bob if you please’

Johnson’s (probably apocryphal) story was by no means unique. The 18th-century violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini was so talented – his remarkably long fingers allowed him to play three octaves across four strings – that suspicions of devilish presence allegedly provoked his audiences to seek their own protective crossroads, making the sign of the cross to protect themselves. In the 1995 play Paganini, the stage version of the great musician claims to have sold his soul to the devil unwittingly.

Crossroads were also a mainstay on the early modern English stage, especially in an era when capitalism in the form of land enclosure endangered the existence of the itinerant vagrant, and led to their demonisation. In works by writers such as Thomas Nashe, Thomas Dekker and Richard Brome, the vagrant’s habitual places of rest – roadsides and crossroads – are often depicted as a threat to civic order. Written in 1592, Nashe’s Pierce Penniless his Supplication to the Divell sees his eponymous protagonist lament his various misfortunes to the devil. The imagery of crossroads occurs throughout the text.

There is a real sense of force in Angus’ writing style that drives his narrative. His footnotes attest to the multifarious nature of the research behind this original cultural history, revealing the varied paths down which his research has taken him: Angus draws from sources as diverse as the plays of William Shakespeare and Native American and African American ‘Trickster Tales’ (it is possible that among the unintended consequences of the transatlantic slave trade was the importation of African crossroad spirits to the US). We encounter crossroads in 15th-century grimoires, or spell books, as well as in later studies of rugby football.

As is to be expected when dealing with something that exists as much in the imagination as it does in reality, Angus’ study covers a lot of ground, much of it rich in symbolism. A History of Crossroads in Early Modern Culture will reward the attentive reader who is ready to discover that the devil is both at the crossroads and also in the detail.

A History of Crossroads in Early Modern Culture

Bill Angus

Edinburgh University Press 312pp £20

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Patrick J. Murray is a researcher in early modern studies. He is the author of Intellectual and Imaginative Cartographies in Early Modern England , 1550-1700 (Routledge, 2022).