Gutter Press

Why did newspapers maintain a policy of isolationism in the midst of a world embroiled in war?

In 1943 a member of the Roosevelt administration railed against what he called the ‘Newspaper Axis’. With the world embroiled in war, a number of newspaper owners in the US doggedly maintained a policy of isolationism, resisting the president’s efforts to support the Allies. Isolationism often, though not always, went hand-in-hand with conservative domestic politics, such as opposition to Roosevelt’s New Deal. It was also closely tied to racialist worldviews which were suffused with antisemitism and anti-Asian racism.

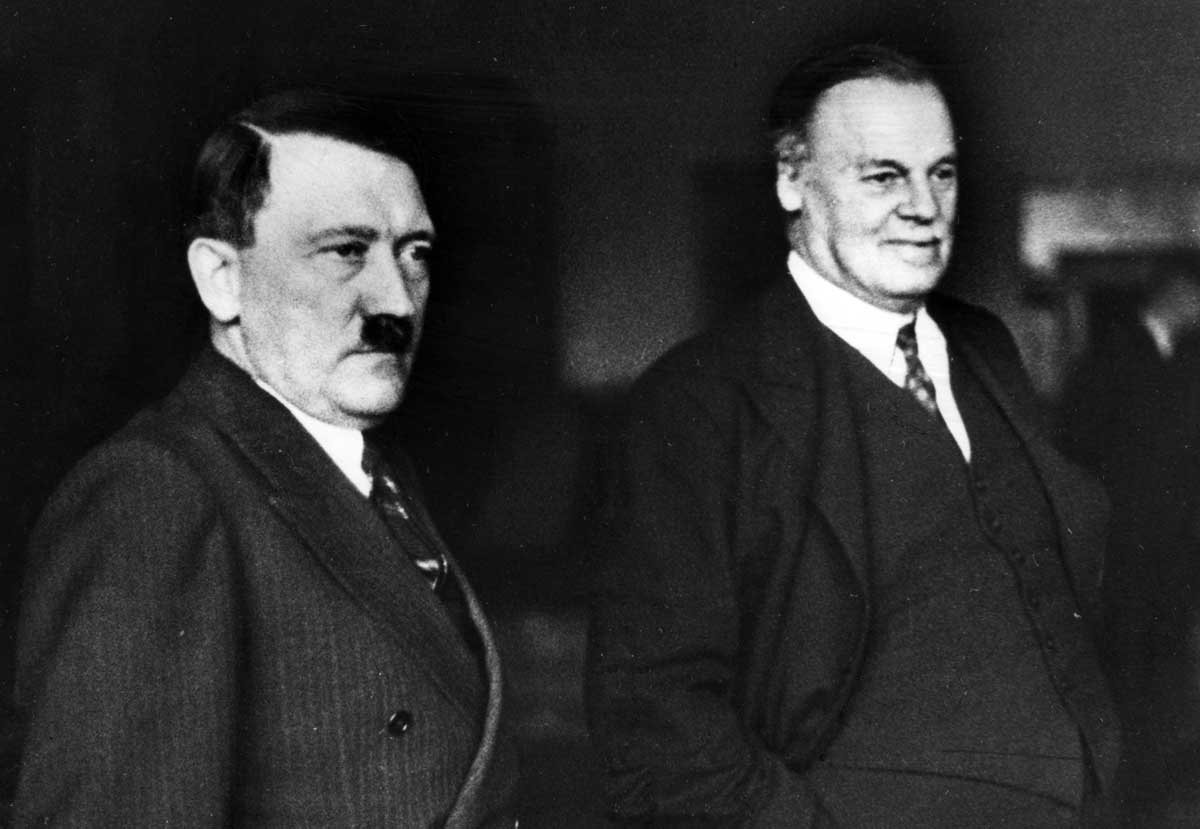

Kathryn Olmsted’s fascinating new book expands the ‘axis’ to include two British press magnates who sought to stop Britain confronting Nazi Germany, Lords Rothermere and Beaverbrook, owners of the Daily Mail and the Daily Express respectively. Rothermere’s dour character and extreme political views are well captured, from his close relationships with leading Nazis, to his support for the British Union of Fascists and his murky relationship with a suspected Nazi spy. Beaverbrook was a much more mercurial figure. Olmsted details his shifting positions, as well as his success in managing to avoid being tarred as one of the ‘guilty men’ of appeasement.

The American contingent is largely a family affair, in the form of brother and sister Joe and Cissy Patterson and their cousin Robert McCormick, who between them owned major newspapers in New York, Washington DC and Chicago. Joe bucked the trend when it came to domestic politics, championing redistributive policies and the New Deal. However, his staunch adherence to isolationism nevertheless meant he became an implacable opponent of Roosevelt, with Cissy following his lead. At times Joe worked closely with Beaverbrook. McCormick was both an enduring isolationist and fiercely anti-progressive in social and economic affairs, while William Randolph Hearst had been radical in his youth, but by the late 1930s had become a staunch adversary of the New Deal and another ardent proponent of isolationism.

The newspapers of these proprietors reached millions and their influence was taken seriously by politicians. Roosevelt, for example, courted other newspaper owners and developed his own propaganda, such as his ‘fireside chat’ radio broadcasts. Yet, whether it was because they were seen as too ephemeral, too vulgar, or just because of the practical difficulties of engaging with the sheer mass of material (something made easier with digitisation), the historical impact of popular newspapers has often been underappreciated. Olmsted is not afraid to make bold claims about the influence of the press, backed by compelling evidence. As the book shows, these popular newspapers and their owners failed to achieve their short-term aims, but they provided a foundation for conservative politics on each side of the Atlantic for decades to come.

The Newspaper Axis is engagingly written and full of interesting details which presage the future course of transatlantic right-wing politics. We are told, for example, how a then little-known author called Ayn Rand wrote to the New York Daily News in August 1942 to rebuke critics who labelled the newspaper fascist. Elsewhere, we learn how a young Rupert Murdoch worked under Beaverbrook at the Express in the mid-1950s. But the book’s real strength is that it takes popular newspapers seriously, demonstrating that, even if their style often seems frivolous, their influence on the course of history is anything but.

The Newspaper Axis: Six Press Barons Who Enabled Hitler

Kathryn S. Olmsted

Yale University Press 328pp £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Aaron Ackerley is a historian of the British press and Teaching Associate at Queen Mary University of London.