Revolting Romantics

The story of a young William Blake warning Thomas Paine of impending danger is one of the great myths of English Romanticism. But did it happen?

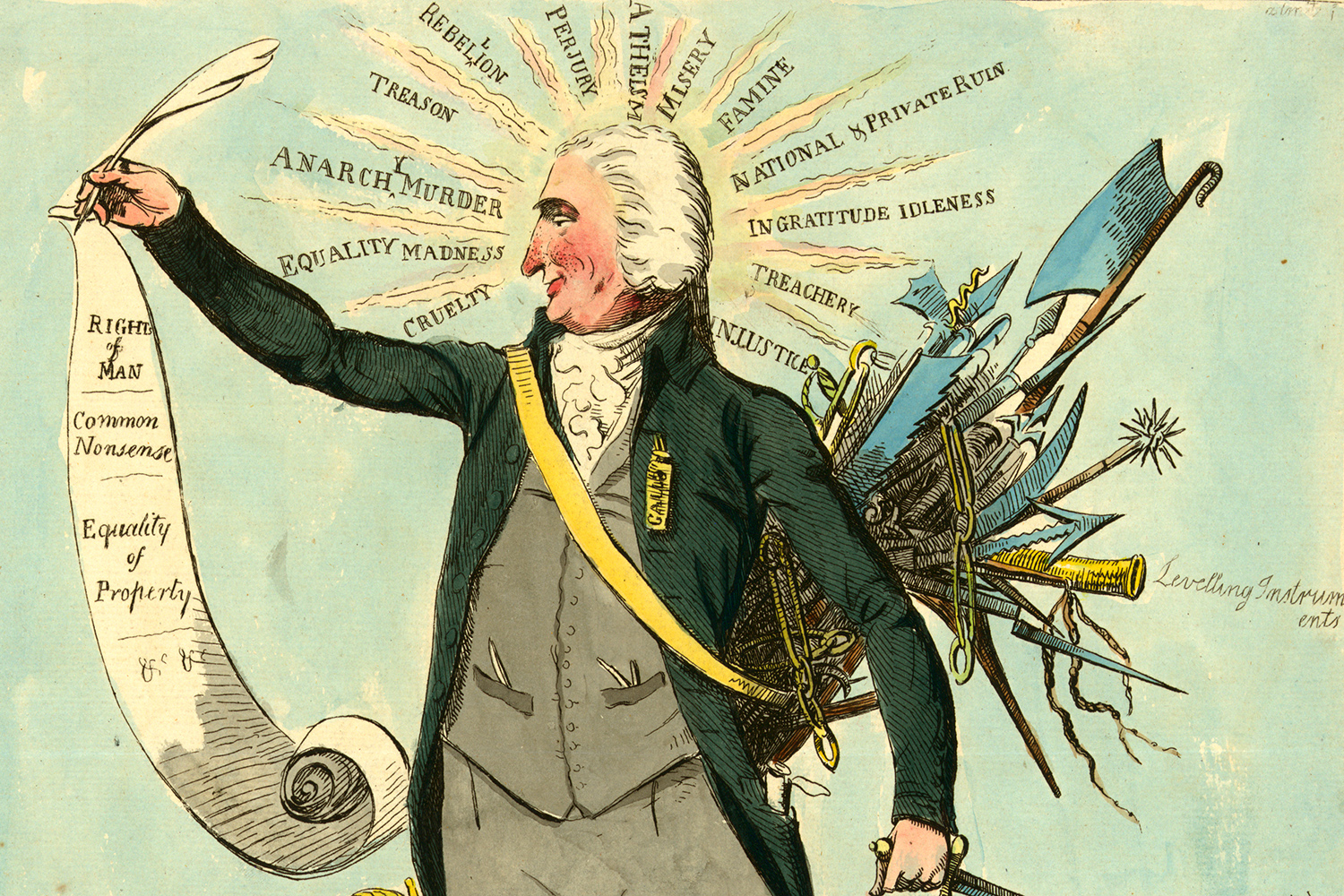

Caricature of Thomas Paine, unknown artist, 26 December 1792.

In 1792, Thomas Paine was 55 and famous, albeit in the manner of a Julian Assange. After emigrating to America in 1774, his career as a radical journalist culminated in the incendiary 1776 pamphlet Common Sense. This single essay catalysed the American Revolution and established its author as one of the founding fathers of the United States. He denounced the hierarchical ‘Crown, Lords and Commons’ of the English constitution, arguing for an independent, egalitarian America. Paine returned to England in the late 1780s and, after a failed career as an engineer, found himself taking up the pen again to defend the French Revolution. Rights of Man was published in 1791 as a riposte to Edmund Burke’s eloquent plea-bargaining for divine moral order. For Paine, ‘rights’ enabled the common man to free himself from despotism. Rights of Man, Part the Second followed in 1792. Already a bestseller, Paine encouraged cheaper editions. He cared as little for royalties as he did for royalty.

By contrast, the 34-year-old William Blake was singularly obscure. A professional engraver and budding poet, he had self-published Songs of Innocence in 1789, but his career was still ahead of him. Both Blake and Paine were friends of the radical publisher Joseph Johnson and became acquainted at his bookshop at 72 St Paul’s Churchyard, London. Legendary suppers were held in an upstairs room where Henry Fuseli’s masterpiece The Nightmare hung on the wall, alongside Fuseli’s portrait of the radical chemist Joseph Priestley. William Godwin and Mary Wollestonecraft were also regulars.

The possibly apocryphal story suggests that at one such dinner, Paine reprised one of the firebrand speeches he liked to make in rooms above pubs. Dull it wasn’t. Paine was intoxicated by his own success as well as his mission to herald a new dawn for humankind. A favourite refrain was: ‘We congratulate the French nation for having laid the axe to the root of tyranny.’ England needed to revolt accordingly and overthrow its class-ridden decadence. While his audience applauded, Blake was concerned for Paine’s safety. According to Blake’s friend, Frederick Tatham, Blake said to Paine: ‘If you are not now sought, I am sure you soon will be.’ The biographer Alexander Gilchrist in The Life of William Blake ‘Pictor Ignotus’ (1863) went as far as to claim that Blake ‘laid his hands on the orator’s shoulder, saying: “You must not go home or you are a dead man!” and hurried him off on his way to France.’

Though disputed, the story has since been repeated by scholarly biographers. John Keane writes of Paine that ‘his friend William Blake tried to convince him that the reign of terror placed his life in serious danger. Blake had just been told of the rumour that a warrant had been issued for Paine’s arrest.’ G.E. Bentley’s Blake Record is a compendium of every known fact about Blake. He explains: ‘Blake certainly associated himself with “the Paine set”, and his friends, at least, believed that he was responsible for Paine’s escape from England on 12 September 1792, just steps ahead of a vengeful government.’

Regardless of its veracity, it has become a beloved myth. It differs from the usual Romantic vistas: Wordsworth gazing at lakes, Coleridge loaded on opium. Here, what Karl Marx called ‘the day of danger’ has come and a philosopher and poet are seen trying to outmanoeuvre the forces of repression. The evidence for the myth, however, is anecdotal. Alexander Gilchrist had diligently interviewed some of Blake’s acolytes, but Frederick Tatham was 50 years younger than Blake, and so could not have been present on the night in question. He was also a reactionary, who had no wish to stress Blake’s association with Paine. Another of Blake’s followers, the spiritual painter Samuel Palmer, offered a similar viewpoint: ‘Blake rebuked the profanity of Paine.’

These first-hand testimonies confirm a companionship. Blake was a trusted member of Paine’s circle, a friend with whom he could debate political reformation and religion. We know from Blake’s prolific marginalia that he had read Paine omnivorously. He regarded Paine as a miracle worker, comparing Common Sense to Christ’s feeding of the 5,000. Blake, a hosier’s son, had problems in his youth when mingling in genteel circles. In Paine he found not only a companion who was earthy to the point of vulgarity, but a writer who had degentrified the language of intellectual discourse. John Keane memorably calls Paine a ‘burping farting’ insurgent. Blake too revelled in scatology. ‘Then old Nobodaddy aloft / Farted and belched and coughed.’ When Blake writes ‘Paine is either a Devil or an Inspired Man’ – in the margins of his copy of Apology for the Bible (1798) by Bishop Watson – it evinces personal knowledge and is the highest compliment.

Paine, as a much younger man in London, had been lucky enough to be mentored by Benjamin Franklin, who was also of relatively humble origins. Thus Paine, the son of a staymaker, might have looked kindly upon Blake. They were both members of that tribal class, the artisan-craftsmen. Both had grown up knowing hard work and political dissent. Furthermore, both were poets. Paine was accomplished but – unlike Blake – was too afraid of the imagination to commit to it. Already he was meditating on what would become The Age of Reason (1794). Paine preferred reason to revelation; Blake believed in ‘The Poetic Genius’ as the timeless source of inspiration.

That Paine had a huge influence on Blake’s poetry is clear from the latter’s oeuvre. In 1793, Blake wrote an 18-page poem, America a Prophecy, eulogising the American Revolution and namechecking Paine no less than four times. Paine, a brilliant wordsmith, also influenced Blake’s vocabulary. The first draft of ‘London’ reads: ‘I wander through each dirty street / Near where the dirty Thames does flow.’ After reading Paine in Rights lambasting ‘chartered monopolies’, Blake amended his opening adjective to ‘charter’d streets’ and ‘charter’d Thames’. Conversely, after Paine in the final peroration of Rights envisaged ‘political summer’, Blake looked around at William Pitt the Younger’s England and wrote: ‘It is eternal winter there.’

It is possible that Blake went further and invented a character based on Paine. ‘Orc’ is Blake’s personification of revolt. When in chains he is frustrated and ferocious; when unchained, it signals revolutionary tumult. The red-faced, drunk, raucous Paine provided the perfect raw materials for Blake’s fiery demonic figure. As Orc – in successive Blake epics – appears first in America and later in Europe to foment uprising, so Paine bestrode the two continents in a similar role. (Blake, who never left England, must have been impressed by Paine’s globetrotting). Blake’s graphic images of Orc even resemble a naked Paine with brownish curling locks and aquiline nose.

In 1791 the two men shared something else in common: a major disappointment. Joseph Johnson was all set to publish books by both of them. Proofs appeared for Paine’s Rights of Man and for an epic poem by Blake entitled The French Revolution, the first of seven books. This would finally launch the late-blooming Blake as an English poet of renown. Instead of engraving for Johnson’s authors, he would become a Johnson author. It was not to be. Johnson found himself intimidated by government agents and pulled out on the day of Rights of Man’s publication. Paine recovered and found another publisher, J.S. Jordan of Fleet Street. It is not known why Blake’s poem was also pulled, but Johnson was running scared. Unfortunately, Blake’s proofs were not picked up elsewhere. While Paine became the most sought after literary man in England, Blake lapsed into lifelong obscurity.

On 21 May 1792 Pitt passed a Proclamation Against Seditious Writing. On the same day Paine was charged with seditious libel for his authorship of Rights and ordered to appear in court in a fortnight. Demonised, Paine became more demonic. Frisson followed his every move – and spies. If Blake and Paine had a drink at the Angel Inn, Islington, they’d have been observed. The Times branded him as ‘Mad Tom’. Other broadsheets claimed to have intercepted messages ‘from Satan to Citizen Paine’. Effigies of Paine were burned in the streets, perhaps inspiring Blake’s vision of Orc in flames. Even Paine’s friends called him ‘the Demogorgon’. Surprisingly, Paine’s trial was postponed from May to December. What few realised was that the government wanted Paine to go into exile. They were afraid of public reprisals for punishing him, riots, perhaps even revolt.

By September, Paine, though defiant, was on tenterhooks. It was at that point that Blake reportedly issued his warning. If he did, it hit home. Paine travelled by night coach to Dover on 13 September. (Bentley claims it was 12 September, which is perhaps the date of Blake’s intervention.) Customs proved difficult, documents were seized and Paine feared arrest. Finally, an official muttered an apology and Paine sailed to France, now understanding the game. A show trial found him guilty in absentia.

It was a learning curve for Blake. A decade later, on 12 August 1803, in Felpham, Sussex, he was charged with sedition for insulting a soldier. The paranoid Blake felt that the government had stitched him up and worried about the gallows. All the prosecution had to do was cite Blake’s association with Paine and the London radicals. They didn’t. Blake was exonerated by jury.

Niall McDevitt is a poet and essayist.