Who’s Afraid of the Jazz Monsters?

For many Americans, jazz was the music of demons, devils and things that go bump in the night.

Moral panic in 1920s’ America was expressed in headlines such as one from the Kansas City Kansan of 16 January 1922 that trumpeted the perils of ‘Vampires, Jazz, Joyrides [and] Turkish Immorality’.

While ‘vamps’, motorcars and Eastern influences were favourite targets of the press, the fiercest language was reserved for jazz. By the early 1920s, jazz was all the rage, bringing not only a new musical language, but a new way of life. The censorious public discourse connected jazz with insanity, drug addiction, chaos, the primitive and bestial, criminality, infectious disease, the infantile, the supernatural and the diabolical. Across the United States, writers, politicians, music educators, critics and ministers framed jazz as a monstrous threat.

Vampires (‘vamp’ in its less alarming form) were one type of monster associated with the jazz lifestyle. Vamps were dangerous, liberated women, who, just as in postwar France, Germany and Britain, embraced the dances, underworld, daring fashion and openly seductive behaviour that critics associated with jazz. This change of ‘vampire’ from folkloric monsters to human women was rooted in Rudyard Kipling’s 1898 poem ‘A Fool There Was’. Often reprinted in American newspapers as ‘The Vampire’, the poem about an irresistibly seductive woman was written as promotional material for Philip Burne-Jones’ painting of the same name. Soon shortened to ‘vamp’, the image was widely adopted in silent film, eliding exoticism, Orientalism and the supernatural. By the 1920s, vamps were closely connected to the emerging jazz culture. As early as 1919, the Oakland Tribune ran a lighthearted column declaring that ‘jazz vampires’ were the ‘new thing’, the ‘antithesis’ of the silent film vamp Theda Bara’s ‘soulful’ version.

The Jazz Age vamp was more detached from the Orientalist and supernatural overtones of her silent film incarnation, but the term – sometimes with its sinister origins – persisted in popular culture. Although many Americans playfully embraced the vamp concept, critics of Jazz Age culture still found her (and occasionally, him) disruptive. The popular film vamp Nita Naldi summed up the figure in a 1924 Los Angeles newspaper interview, using the term in its startling entirety: ‘Upon jazz music, vampires and a natural restlessness inherent in the American people rests the blame for the spirit of disquietude which has inundated the country.’

Other, more heavy-handed public rhetoric framed 1920s’ jazz not merely as a source of disquiet, but of terror. Katherine Willard Eddy of the Young Women’s Christian Association stated in a 1920 address at the University of Wisconsin that ‘We are in deadly fear of the Jazz Devil, the demon which is consuming the country.’ A 1921 notice in the Logansport Pharos-Tribune assured readers that ‘the whole world is rising in arms against the monstrous jazz and its finish is not far removed’. In 1922, noted Denver lawyer and Prohibition crusader John Hipp described jazz dance halls as ‘ticket offices to hell’. That same year, a Charlotte Observer columnist moaned, ‘Where can we hear music that is not of the hellish jazz?’ And in 1925 the American music critic Carl B. Adams declared that, before the bandleader Paul Whiteman’s interventions, ‘a jazz band formerly was a diabolic contraption for the production of weird notes and heinous discords’, a collection of sonic ‘terrors’. Whiteman, Adams noted, had ‘removed the deadly fangs from the mouth of the monster jazz’.

Despite this bluster, American jazz musicians and composers appropriated the notion of the diabolical and the monstrous into excellent PR. Popular jazz songs featured the vamp figure, including a 1920 recording of ‘I’m a Jazz Vampire’ by Marion Harris (an obvious modification of her 1919 hit ‘I’m a Jazz Baby’). Iconography of vamp songs sometimes played on the exotic and the supernatural: the cover of the 1919 sheet music ‘Be My Little Vampire’ featured a dark-haired woman partly obscured by a bat in the foreground and superimposed over a misty moon. Groups called themselves the Jazz Devils and the Black Devils Orchestra (possibly a racialised reference). The 1923 song ‘Come On Red, You Red-Hot Devil Man’, with a leering man on the cover, attested to the thrill of the supernatural. And, as late as 1929, the Midwest Vaudeville Exchange listed among its available acts a ‘vampire jazz singer’.

What does it mean that this constellation of loosely Gothic language hovered like a miasma over 1920s’ jazz culture, used in jest by its practitioners but in deadly earnest by its critics? As the literature scholar Jerrold E. Hogle writes, the modern Gothic sensibility came to ‘connote a backward-leaning countermodernity lurking in both the emerging and recent stages of modern life. This retrogression appears to undermine, and in that way “haunt”, the assumption that the “modern” has left behind any regressive tendencies that might impede its progress and fulfillment’.

When the critics of 1920s’ jazz framed the music and its lifestyle as a hellscape populated by demons and vampires, they imagined themselves part of a modern Gothic drama, with jazz a regressive monster haunting ‘progressive’ American culture.

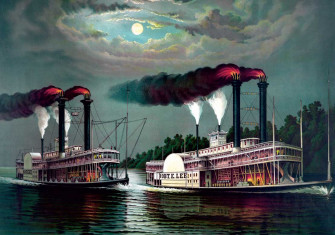

And, just as the 19th-century Gothic imagination located terror in the attic, the moor, the crumbling castle and the ruined abbey, 1920s’ critics often linked the jazz threat to the swamp and the jungle. In a widely published 1922 sermon titled ‘Is Jazz Our National Anthem?’ an Episcopal rector from New York stated: ‘Jazz goes back to the African jungle and is one of the … evils of today … [its] savage crash and bang … is retrogression … [which] makes you go “back to all fours”.’ A 1925 article in the Brooklyn Daily News alluded to jazz’s ‘jungle’ roots: ‘Through the almost impenetrable walls of that African fastness this strange musical insurrection has spread to all corners of the globe.’ A 1925 news article compared jazz to ‘squalls of jungle beasts in the mating season’. In a newspaper interview in the late 1920s, even the avant-garde dancer Isadora Duncan rebuked the entire US for its embrace of ‘the monstrous jazz rhythm of the primitive savage’.

It was, of course, jazz’s African-American roots that provoked language describing the music as monstrous. Jazz critics of the 1920s saw the syncopated, danceable music as a racialised, premodern threat to traditional ways of life. In the end, the terror that jazz held for them says far more about the critics than about the music. Our monsters always show us what we fear.

Carrie Allen Tipton writes about American history, pop culture and music.