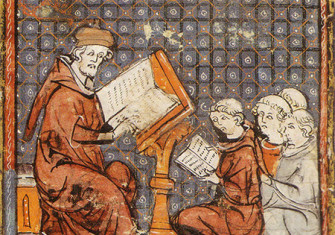

Inside the Anglo-Saxon Classroom

Schoolboys forget their books, lose their pens and laugh at dirty jokes. This was true even in the rigorous atmosphere of the Anglo-Saxon classroom.

As with all things relating to Anglo-Saxon England, evidence of what happened in the classroom is scant, but what does survive paints a familiar picture. Education in that period came in many shapes and forms: some students took apprenticeships and learned practical skills, while others went into monasteries and learned to read and write. King Alfred believed that all the youth in England should be taught to read and write in English and those continuing into the monasteries should learn Latin. The teaching of Latin saw a revival in the 10th century, amid worries that the state of learning in England had declined until it seemed as though not a single priest in England was able to compose in Latin or indeed, read it.

No books survive which are definitively known to have been used in the classroom, but we have some idea of the types of texts used. The curriculum used for teaching Latin had its roots in classical teaching models. It used three main methods: glossaries taught vocabulary, grammars taught syntax and morphology (the structure of language) and colloquies – scripted conversations – gave conversational practice, in which students could put their vocabulary and structural learning to use. This combination is still recognisable to anyone who has taken a modern language course.

The works of two of the greatest teachers from the late 10th century give us the best insight into the Anglo-Saxon classroom and curriculum. Ælfric of Eynsham (also known as Grammaticus or the Homilist) wrote a glossary, a grammar and a colloquy for the teaching of Latin with a parallel text in Old English, an innovation that made it more accessible for students yet to learn Latin. The only student we can confidently say to have come from Ælfric’s school is Ælfric Bata (Bata seemingly a nickname from the Hebrew for ‘barrel’, either being a reference to his size, or to his love of drink). Bata wrote a colloquy which followed his teacher’s model but in a different style. Where Ælfric’s work upheld the monastic lifestyle and ideals, Bata’s was raucous and dramatic.

Bata’s colloquies are intended for students to learn Latin through the use of dramatic scenes in which aspects of daily life in the classroom are played out: in a normal day, the master or his helper would give each pupil a passage of about 40 lines to memorise and recite back the following day, with the threat of a beating if this was not performed satisfactorily.

As well as allowing students to play out the roles of teacher and student, or farmer or tradesman, Bata writes of monks throwing alcohol-fuelled parties, negotiating kisses from women, riding into town to get more beer and going to the privy with younger pupils, unaccompanied. His scenes often directly break the Benedictine rules to which Bata and his pupils were expected to adhere. In one colloquy, he sets out a dialogue between master and pupil in which they exchange a vast array of scatological insults, including the memorable ‘May a beshitting follow you ever’. Certainly, his pupils were not going to forget the relevant vocabulary.

In addition to learning to read and speak Latin, students were also expected to learn to write and shape their letters to a high calligraphic standard in order to produce manuscripts. At the earliest stages, they learned to form the shapes of letters by copying examples from their master, writing on wax tablets with a stylus and a knife to scrape it clean, or on scraps of parchment or vellum left over from the production of full manuscripts. Because these early stages were informal and the scraps probably meant to be discarded, none have survived, although tablets have been found in Ireland and styluses at Whitby. Examples of the work of more advanced students can be seen in manuscripts made at the scriptorium of St Mary Magdalene in Frankenthal. Here, the master starts at the top of the page to demonstrate the style, layout and script of the page and the pupil takes over, shakily at first. The two hands then alternate in sections down the page, as the pupil improves. When students were deemed good enough, they would be asked to produce manuscripts for their monastery, or they could work for their own benefit. In one scene from Bata’s colloquies, an older student barters and gains a commission to copy a manuscript for a fee of 12 silver coins.

Education was highly valued among Anglo-Saxons. Yet, despite its serious purpose, schoolboy humour remains evident throughout. In that sense at least, the classroom has changed very little in the last thousand years.

Kate Wiles is a contributing editor at History Today.