The Legacy of 1815

Are we in danger of neglecting the true importance of one of history’s epochal years?

Waterloo holds our attention, but there were other episodes in British military history that year which were also important in framing the ‘long 19th century’.

The most obvious was the defeat in January of Wellington’s brother-in-law, Sir Edward Pakenham, outside New Orleans, which underlined the extent to which war between Britain and the US would end in compromise. Indeed, a peace had already been negotiated at Ghent, although it had not yet been ratified. As the campaigns of 1812, 1813 and 1814 demonstrated, Britain could hold Canada against US invasion. Moreover, the Americans were not strong enough at sea to inflict fatal damage on the British maritime blockade. Equally, British attempts to co-operate with Native Americans had little success and British invasions of America struggled to achieve lasting results.

One legacy of 1815 was, therefore, a North America in which Britain was going to have to accommodate a rapidly expanding new state. The implications were realised mid-century, when the US extended its rule to the Pacific and overcame secession.

The year also delivered an effective demonstration of British strength in the western hemisphere. Overshadowed by Waterloo, the British capture of the French colonies in the West Indies indicated that Britain’s capacity for power projection was unrivalled, a situation that continued until the Second World War. The sugar islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique had been returned to French control as part of the peace settlement in 1814, having been seized by British amphibious forces in 1810 and 1809 respectively. They were attacked anew in 1815.

Against Martinique, Lieutenant-General Sir James Leith, governor of the Leeward Islands and commander-in-chief in the West Indies, sent troops from nearby St Lucia. They landed on June 5th, occupying all key positions. In Guadeloupe, the situation proved more difficult. An insurrection, mounted on June 18th, ironically the same day as Waterloo, succeeded with the support of the local authorities and Napoleon was proclaimed emperor the next day. In response, Leith landed his men on August 8th. His forces advanced rapidly and, two days later, the French surrendered. Leith had been helped in his task by bringing news of Waterloo.

British naval strength was also displayed in French waters in 1815. France was blockaded by the British fleet and, under the command of Major-General Hudson Lowe, later Napoleon’s custodian on St Helena, British forces at Genoa co-operated with a squadron under Edward, Lord Exmouth, the commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean, to occupy Marseille. In conjunction with local royalists, they then advanced on Toulon, restoring it to Bourbon control.

The Royal Navy also denied Napoleon his own freedom. Napoleon planned to go to America, but found himself trapped at Rochefort, from where he boarded HMS Bellerophon on July 15th, throwing himself on the ‘generosity’ of the Prince Regent. Instead, he was taken to Torbay, where he was not allowed to land, transhipped and taken to imprisonment on St Helena, a South Atlantic outcrop made secure by Royal Navy dominance.

Another aspect of British strength was apparent in 1815, notably the budget presented to the Commons on June 14th, at a time when the likely duration of the war with Napoleon was uncertain. This budget made provision for the expenditure of £79,893,300, which was to be met by the renewal of the war taxes, as well as by new loans. In South Asia, the British continued to demonstrate their strength, conquering that year the kingdom of Kandy, which had earlier defied the Portuguese, Dutch and, indeed, in 1803, the British.

In the longer term, these elements proved more significant than Wellington’s triumph at Waterloo. The limited size of its peacetime army affected what Britain could do on the Continent after 1815. British forces were sent there, notably to Portugal, but there was, as for Wellington in Portugal, Spain and at Waterloo, a reliance on coalition warfare for anything more than peripheral operations, a reliance repeated in the Crimean War (1854-6).

At sea the situation was very different. Britain was by far the leading naval power and was to maintain this position despite the disruption and cost arising from repeated changes in naval technology, notably to steam and iron. The development of countervailing weapons and techniques, such as shell guns by the French in the 1830s, did not lead to the overthrow of the British position.

Naval dominance ensured that Britain was best placed to take advantage of an integrating world. It was the British character of globalisation that proved so significant to the world in the 19th century, helping ensure that British influence was not simply a matter of Empire, whether formal or informal.

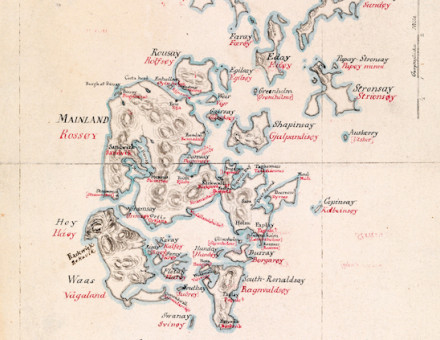

In part, the British world was grounded on force, but its purpose was peaceful, notably as an agent of economic growth. Maritime trade appeared to the British to be their destiny and a means of global good, and free trade acquired totemic significance. The charting of the oceans combined the search for information, its accumulation, depiction and use. Britain’s global commitments and opportunities, both naval and commercial, made it easiest and most necessary for it to be Britain that was acquiring and using the information. Veterans of the Napoleonic war played a major role in the early surveying.

In addition, tide prediction tables expanded dramatically from the 1830s. Improvements in equipment and representation played a role, notably the development of the self-registering tide gauge, which was able, by tracing all tidal irregularities, to provide the accurate data necessary for a dynamic theory of the tides.

William Whewell, a major member of the British scientific élite, who played a key part in the work on tides, also applied himself to creating a self-registering anemometer to record the velocity and direction of the wind. Despite the development of steam power, knowledge of the wind remained significant for navigation.

All this information was integrated, so that the world was increasingly understood in terms of a western matrix of knowledge in which Britain played the key role.

The advantage offered to British power by technological developments, by information systems, especially the accurate charting and mapping of coastal waters, and by organisational methods, notably naval supply depots, gave Britain an unsurpassed global reach. It became possible to envisage the construction of a global system, with the British Empire as its framework.

The range of knowledge acquired was shown in careers such as that of Clements Markham (1830-1916). He became a naval cadet before being sent to Peru by the India Office in 1859 to collect seeds and young specimens of varieties of the cinchona tree (from which quinine is made). Once established in southern India, this production resulted in a marked fall in the price of quinine, which encouraged its use by Britain. Malaria rates fell. Appointed to the Geographical Department of the India Office in 1868, the year in which he served as geographer on the military expedition to Ethiopia, Markham served as President of the Royal Geographical Society from 1893 until 1905.

Britain’s position was under challenge before the Great War. In January 1904, after hearing a lecture by Halford Mackinder to the Royal Geographical Society on rail links across Eurasia, Leo Amery, later a Conservative politician, emphasised the onward rush of technology and the resulting need to reconceptualise space. He told the society that sea and rail links and the subsequent global distribution of power would be supplemented by air, leading to a new world order.

Amery’s assumptions were not vindicated for a while: Britain, despite the rise of the US, was a stronger power in relative terms in the 1920s than it appeared to be in the 1900s, though that was soon to change. But the legacy of 1815 was real and, thanks to the character of British power, the Western-dominated world of the 19th century was more liberal, politically and economically, than it would otherwise have been.

Jeremy Black's books include The Power of Knowledge: How Information and Technology Made the Modern World (Yale, 2014).