The Origins of English Parliament

The English Parliament was purportedly founded on 20 January 1265. Why is this date so significant?

English Parliament is said to find its foundation 750 years ago today (January 20th) when, following a civil war with Henry III, Simon de Montfort, 8th Earl of Leicester, called together a parliament of knights and burgesses, representatives of local towns, to discuss wider matters of English governance. Yet despite this landmark date, Montfort’s parliament was not the first such gathering in English history.

The Anglo-Saxons, understanding the need for decentralised power beyond the immediate reach of the king, used a system called the witangemot, the meeting of the royal court based on Carolingian models of governing. The witan met in regional localities to discuss issues beyond the scope of everyday matters of government. It moved around the country; the majority were held in the south of England, focused on Winchester and London, with rare trips further north to Nottingham and Lincoln. The names of those present at a witan were recorded in lists of witnesses to land-grants, which show that, for example, in the reign of Æthelstan (927-39) sometimes up to as many as 100 were in attendance. The king’s rule was wholly entangled with the Church, so while the meetings were secular and attended by thegns, ealdormen or earls and other noblemen, bishops and abbots also attended to offer religious counsel. The king was present to witness and validate the declaration of law, but that is not to say that the king was solely responsible for law-making: it was a process of discussion, with many voices.

Other processes connected with Parliament, such as record-keeping and the treasury, are less easily defined: the presence and form of the royal chancery - the scribes and record-keepers who accompanied the witan and produced its charters and grants - are the subject of an ongoing and seemingly unending debate among scholars and the origins of the English treasury have been described by Warren Hollister as ‘mysterious as the migration of eels’.

In his magisterial work of 2010, The Origins of the English Parliament, 924-1327, J.R. Maddicott sees the witan as the earliest origin of England's modern Parliament, as it began the process of allowing small collections of representatives to set the laws for the whole country.

This foundation was built upon following the Norman Conquest, as William I preserved many of the structures set in place by the witan, but also increased its attendance by obliging all landholding tenants to be present, a move which brought in a larger portion of the non-elite population and resulted in the king coming under greater accountability. The effects of this can be seen in Magna Carta (1215) which holds the king accountable to his subjects. Thus, the Parliament of 1265 did not appear fully-formed without reference to these early models, but was built following their design.

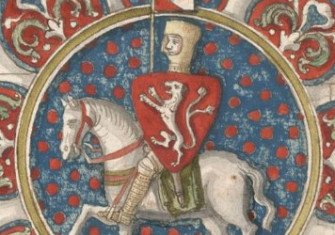

Simon de Montfort, the man credited with calling the first English Parliament, had a tempestuous and inconsistent relationship with Henry III, in turns close and fractious, due to Montfort’s marriage to Henry’s sister Eleanor, debts incurred on both sides and Monfort’s repeated bids for increased power. Ongoing feuds with Henry and the noblemen loyal to him came to a head in the Battle of Lewes in 1264, in which Montfort was victorious and took Henry and his son Edward prisoner. With this moment of power, Montfort used the opportunity to cement it by calling together all those barons who were still loyal to him along with representatives from the shires and towns of England, a move which can be seen as a direct descendant of the Norman inclusion of tenants in the process of government. Despite this, his brief hold on power was short-lived as: in May, Edward managed to escape and soon after defeated Montfort and his supporters. Upon taking the crown, though, Edward I adopted this system of Parliament.

As has been pointed out by Marc Morris in his insightful blog on today's anniversary, Simon de Montfort’s Parliament of January 20th 1265 was by no means the first, so what makes this one notable? Morris argues, not much. Montfort’s Parliament was not the first to call on wider members of society than just the barons and the bishops, nor is it likely that his was the first to meet to discuss more than taxation: the Anglo-Saxon witan and the Norman assemblies both dealt with wider issues of governance. Equally, Morris argues, it cannot be held up as the start of a democratic Parliament as Montfort gained his power by imprisoning the king and his son and used Parliament to cement his power by gathering only those loyal to him.

The tradition of English parliament is long-standing and constantly changing, and its roots can be traced back to the start of England and to a system used across medieval Europe. Today, though notable. marks the anniversary of just one stage in the evolution of English Parliament.

Kate Wiles is contributing editor at History Today.