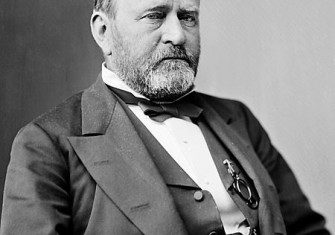

Ulysses S. Grant: Great Soldier but Poor President?

A vast biography of General Grant questions received opinions, while a new edition of his memoirs confirms their historic status.

Ulysses S. Grant is considered one of the great commanders in history and one of the worst US presidents. These two volumes offer the opportunity for a reassessment of that verdict. Grant emerges from them with his career as a soldier untarnished and with posterity’s verdict on his presidency revised. Grant appears as an admirable but all too human being, a truly great man on a par with Lincoln.

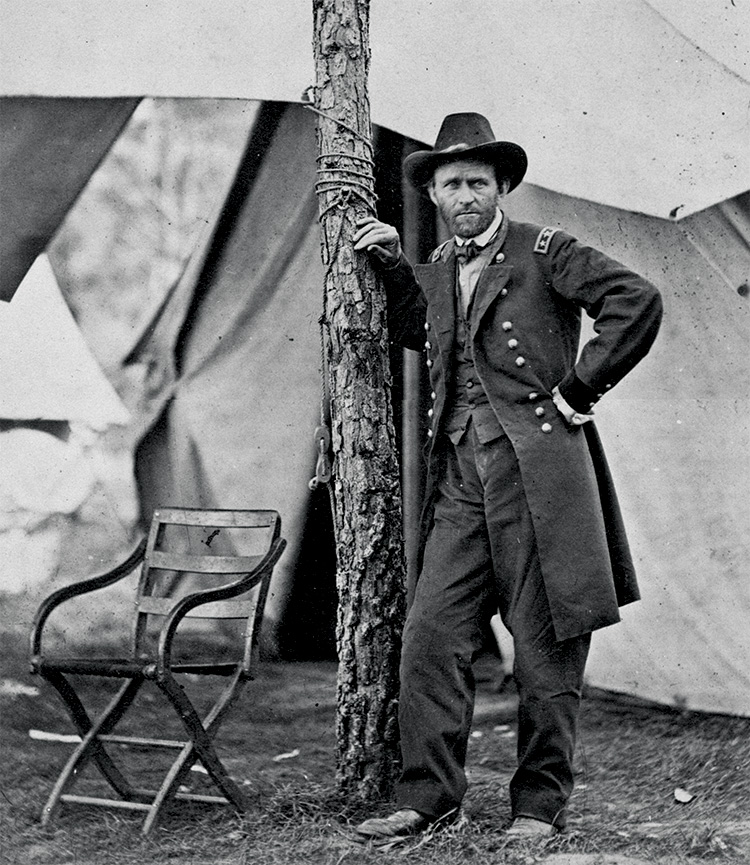

Ron Chernow, acclaimed biographer of Alexander Hamilton, gives us an unvarnished Grant in all his rough-hewn glory. A mid-westerner, Grant went to West Point to please his overbearing father. Though a brilliant horseman, he displayed no particular military ability or enthusiasm and after service in the Mexican War left the army under a cloud because of his drinking.

The outbreak of the Civil War found him at a low ebb: reduced to clerking in his family’s leather goods store. There were doubts about his drinking, but the Union needed trained officers and Grant was given a regiment of volunteers to lick into shape. His rise was rapid. His first achievement was taking the vital Forts Donelson and Henry. When the Confederate commander, Simon Buckner, a West Point friend, proposed meeting as gentlemen to discuss terms, Grant returned a typically terse reply: ‘No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.’ Buckner duly buckled.

The bloody two-day battle of Shiloh tested Grant’s mettle. The first day went to the Confederates and when Grant’s comrade-in-arms, William Sherman, found the general that night and remarked that the day had not gone well, Grant agreed, but added: ‘Whip them tomorrow though.’ He did. Lincoln perceived his quality and when Grant’s jealous enemies plotted to sack him, responded: ‘I cannot spare this General. He fights.’

Grant’s siege and seizure of Vicksburg, key to the Mississippi, crowned his western triumphs and split the Confederacy in two. Lincoln brought him east and gave him command of the Army of the Potomac with the mission to defeat Robert E. Lee, capture the Confederate capital, Richmond, and bring the war to a victorious conclusion.

Grant succeeded, but only after a bloody campaign of attrition which has cast a shadow over his reputation, with some seeing him as a forerunner of Haig in the First World War: a butcher, careless of his men’s lives, who won only by weight of numbers. Chernow refutes this canard and his hero worship of the subject shines from every page of this superb study, but it does not blind him to Grant’s faults.

Like Napoleon, Grant concentrated his forces where they were most needed, was bold to the point of recklessness and was as dauntless in defeat as he was magnanimous in victory. But these strengths were balanced by a tunnel vision in which, absorbed by his own plans, he did not always see how the enemy would react. And he was naively trusting of others, a failing that led him into bankruptcy more than once.

Chernow devotes as many pages to Grant the reluctant politician as he does to the triumphant soldier. Grant has been seen as a bad president, his two terms marred by graft and corruption. While admitting these facts, Chernow prefers to present him as a generous, unifying figure, intent on healing the wounds of the Civil War, and a late convert to the cause of advancing African Americans to an equal place in society.

His memoirs, presented at last in an impressive scholarly edition by John F. Marszalek, were the fruit of a last triumphant battle. In retirement, Grant was hit by three staggering blows: a fall left him crippled; he lost his fortune in a Ponzi scheme promoted by one of his sons; and, after a lifetime smoking cigars, he was diagnosed with terminal throat cancer.

Bloody but unbowed, he set to work on his memoirs in a bid not to ensure his place in posterity, but to provide for his family after the end he knew he was facing. It was a revelation. His inability to speak publicly was transformed into prose as plain and clear as his battle orders. In a publicity campaign organised by Mark Twain, the book was hawked door to door by veterans and became both a bestseller and a classic of military history.

It was left to others to assess his place in history. Chernow’s life and Grant’s own words restore him to the pantheon of great soldier-presidents. He stands alongside Washington, Andrew Jackson, Teddy Roosevelt and Eisenhower, a select company to which he has always rightfully belonged.

Grant

Ron Chernow

Head of Zeus 1,074pp £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: the Complete Annotated Edition

Edited by John F. Marszalek

Harvard Belknap 784pp £64.99

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Nigel Jones is the biographer of Rupert Brooke.