The Elusive Byzantine Empire

Though the beginnings of the Byzantine Empire are unclear, its demise is not. The history of the Eastern Roman Empire, from its foundation in 324 to its conquest in 1453, is one of war, plague, architectural triumphs and fear of God's wrath.

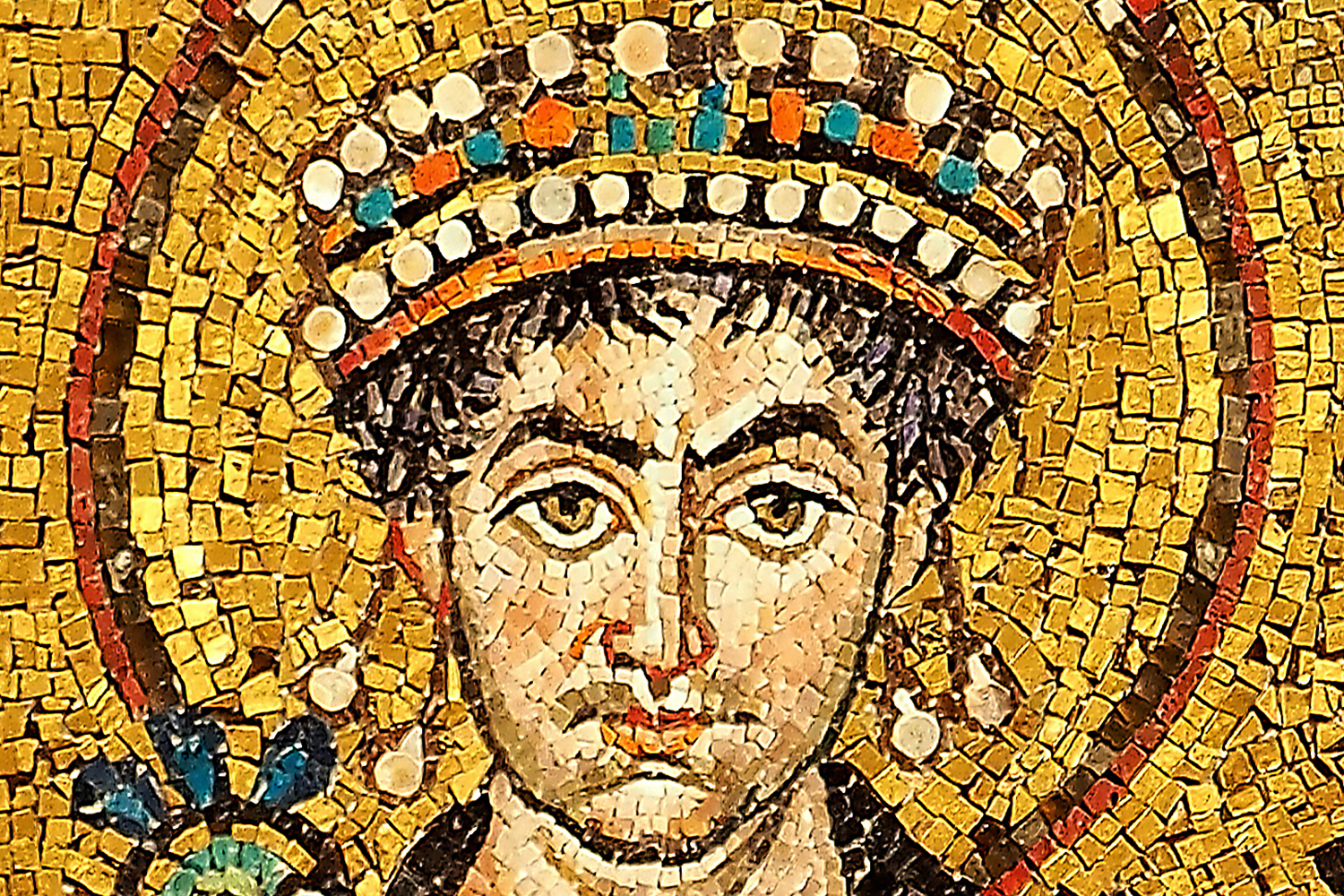

Detail of a mosaic depicting Justinian I in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna.

The Byzantine empire means different things to different people. Some associate it with gold: the golden tesserae in the mosaics of Ravenna, the golden background in icons, the much coveted golden coins, the golden-hued threads of Byzantine silks used to shroud Charlemagne. Others think of court intrigues, poisonings and scores of eunuchs. Most will think of Constantinople, which used to be Byzantium and is now Istanbul, and will possibly bring to mind the city’s skyline with the huge dome of the Hagia Sophia. Little else perhaps exists in the collective imagination. All this is indeed evocative of Byzantium, but there is so much more to explore.

To begin at the beginning is tricky. Did the empire begin when the emperor Constantine moved his capital from Rome to Constantinople in 324? When the city was consecrated by both pagan and Christian priests in May 330? Or did it begin in 395 when the two halves of the vast Roman empire were officially divided into East and West, or even later in the late 5th century when Rome was sacked, conquered and governed by the Goths, leaving Constantinople and the East as the sole heir of the empire? But, if its beginning is unclear, its demise is not: on 29 May 1453, the armies of the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II entered the city and brought the existence of this state to an end after more than a millennium.

When Constantine moved his capital from Rome to the hitherto relatively obscure, though strategically placed, city of Byzantium and gave the city his name, it signalled a shift of interest towards the East, but perhaps little else initially. After the troubled third century a number of cities had functioned as imperial residences without necessarily challenging the idea of Rome as the centre: Trier, Split, Thessalonica, Nicomedia (modern Izmit). But with the advantage of hindsight we can see that this case was different: Constantinople was enlarged, decorated with famous statues and objects from the whole empire (some of which are still in place today), endowed with a Senate and its citizens given the traditional free bread handed out to Romans.

A number of the most important constituting traits of the Byzantine empire date back to this early era. The Byzantine state was, more or less from the beginning, a Christian Roman empire. After the edict of Milan in 313 ended the persecutions and made Christianity a tolerated religion, Constantine showed a marked (though not exclusive) preference for Christianity. He presided over the first ecumenical Council in Nicaea in 325 which defined the creed and dealt with heresies, thus setting the tone for the intimate relation between Church and state. This bond was made clear by a number of sacred buildings that Constantine erected, in his capital as well as in Palestine (both the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the Church of the Nativity go back to this period), and by a number of relics of Christ and the Virgin that his mother, Helena, purchased in the Holy Land and sent back to Constantinople. Unlike Rome or Antioch, the new capital had not been graced by the presence of any apostle, but certainly entered Christian topography with the bonus of imperial patronage.

In the eleven hundred years that separate the first Constantine from the last emperor, another Constantine (the XI), the empire underwent many and significant changes. First came expansion. From the fourth to the early sixth centuries the East flourished: population boomed, cities proliferated and Constantinople itself grew to be the largest city in Europe with over 400,000 inhabitants. To support this growth its city walls were yet again enlarged in between 404 and 413, a triple system of inner wall, outer wall and moat that did not fail to protect it until the very end (large parts of which are still visible, albeit over-restored, today). The ecclesiastical head of the city, the patriarch of the new Rome, had risen to the second position in the hierarchy of the Church just below the old Rome, the result of political pressure that was to breed discontent between the two sees in the centuries to come. Together with Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem they formed the Pentarchy, the ultimate authority of the Church as decided by councils bringing together the senior clergy of the five sees.

While the city expanded, the empire underwent a transformation. In 395, Theodosius I (r. 347-95) divided the vast empire stretching from Britain to North Africa and from Spain to Mesopotamia and harassed by the Persians in the East and Germanic tribes in the North. A demarcation line running roughly from Belgrade to Libya turned, in the fifth century, into a true frontier. In the West, disaster: Huns and Goths overran the Roman world. In the East, Germanic officials were integrated into the government and occupied important positions in the state machinery up until the reign of the emperor Zeno (r. 474-91), when they were gradually excluded by his own people, the Isaurians from the mountains of Asia Minor. The Eastern Empire was an unbroken continuation of the Roman state, though with Greek as the dominant language. The West was now divided into several Germanic kingdoms who adopted Latin for their administration.

Enter Justinian (r. 527-565). The nephew and heir of a parvenu, an illiterate military man turned emperor (for Byzantium was for centuries a quite open society in which one could get ahead in life based on talent), he put an indelible mark on his era. In his time the empire sought to regain the lost territories in the West in a series of long wars. The Vandal kingdom in Africa was subdued in 533-34, but the reconquest of Italy took nearly twenty years until the final defeat and extinction of the Goths in 554. At the same time there was almost constant warfare with Persia, although imperial victories and territorial gains were not as decisive as in the West. But Justinian’s lasting legacy stems from other contributions.

Roman law, the backbone of the administration of such a vast empire, had already been collected and organized in the mid-fifth century. Justinian undertook a review of this massive material early in his reign between 529 and 534. The result was the huge (and hugely influential) Corpus Iuris Civilis which updated the previous Theodosian collection, weeding out all laws no longer deemed relevant, while adding all those passed since that date. It included legal writings of a more theoretical nature and pronouncements that spanned the period from Hadrian (r. 117-38) to Justinian. Ask any lawyer today and you are likely to hear superlatives about this colossal work that has been termed ‘one of the most significant influences upon human society’. Justinian, naturally, continued to legislate and his new laws (the Novels) were issued for the first time in Greek. This was an acknowledgment of the developments that the empire had undergone since Constantine. It was now a state based on Roman law, Christian faith and Greek culture, one in which literacy was widespread and Homer’s Iliad formed the basis of elementary education along with the equally popular book of Psalms.

Justinian was also a great builder. The single most iconic Byzantine building, the Hagia Sophia, is a product of his drive and vision. Completed in 537 after an earlier Theodosian church of the same name had been burned down during civil unrest in the city, the church dedicated to Holy Wisdom is still breathtaking today. The majestic dome with a diameter of about 32 metres gave the impression to contemporaries of being suspended from heaven. This feat of engineering was only surpassed in the 15th century by the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore (Il Duomo) in Florence. The original decoration of Hagia Sophia was not figurative: mosaics with geometrical patterns, deeply cut capitals with the monograms of the emperor and his infamous wife, Theodora, and the interplay of coloured marble on the walls and pavement – all designed to reflect the light as it pierces the space from a multitude of windows. Justinian not only adorned his capital with new buildings; he erected or restored a great number of edifices throughout his vast empire. One of the most famous is the Monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai, still functioning today.

Justinian clearly saw himself as God’s representative on earth. He strove for order and tolerated no dissent; it appears as if he was determined to align everyone to the divine plan for salvation, whether they wanted it or not. The academy in Athens was closed; the Olympic Games and the mysteries in Eleusis had long ceased; and it was probably around this time that the Parthenon in Athens was transformed into a Christian church. Justinian’s unified vision of a Christian empire in a way mirrored a Mediterranean world unified by sea and land communications. This unification, however, allowed not only people and commodities to travel, but also germs. Bubonic plague broke out for the first time in pandemic form in 541 and ran its deadly course throughout the Mediterranean. It was to return in some 18 waves until 750, causing a sharp demographic decline that was felt the strongest in coastal cities. Constantinople lost possibly as much as 20 per cent of its population in four months in the spring of 542.

At the end of Justinian’s reign the empire began to collapse as a result of both demographic losses (from plague and long wars) and economic hardships brought about by these two factors and the cost of large-scale building. By the early seventh century much of the regained territory had been lost. The Lombards invaded Italy in 568 and seized the Po valley; the Visigoths regained the few Byzantine holdings in Spain in 624, while the eastern front collapsed under renewed Persian attacks. Moreover, a new force emerged in the Balkans: the Turkic Avars and the Slavs. From the 580s onwards the Slavs began their settlement of the Balkans, gradually taking almost the entire peninsula de facto out of Byzantine control for the next two centuries.

When Heraclius (r. 610-641) became emperor he raised great hopes that he could restore order and confidence in an empire that seemed in disarray. The Persians captured Syria, Egypt and Palestine between 613 and 619 and, in what must be seen as a calculated move of political warfare, they removed the True Cross of Christ from Jerusalem to their capital in Ctesiphon. Heraclius’ counter-attack took years to prepare. It was almost brought to a halt before it produced any actual results when in 626, while the emperor was away, the Persians with the aid of Avars and Slavs besieged Constantinople. The city was saved, according to tradition, by a supernatural protector, the Virgin Mary, whose girdle had been in the city since the fourth century and who increasingly came to be regarded as Constantinople’s patron saint. After this episode Heraclius took the war to Persia and ultimately defeated the Sassanian king in 628. In a highly significant gesture, he restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in 630.

Byzantium might have been victorious, but the wars that had lasted more than 20 years left both empires exhausted. The timing was perfect for the new emerging player in the Mediterranean, the Arabs. Their expansion began in the 630s. By the turn of the century the Byzantine Empire had irrevocably lost Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Northern Africa, while the Sassanid state had been overthrown. The Arab foray seemed unstoppable. It menaced Constantinople in 678 and again in 717-18, though failing both times to capture the city. The seventh century was a period of massive restructuring and reorganization as the Byzantine empire fought for its survival. The massive loss of territory – especially Egypt, the ‘granary of the empire’ – deprived the state of considerable human resources and commodities.

From then on Byzantium concentrated on Asia Minor as an almost exclusive source for both. A large-scale reorganization of the army took place in that period, first in Asia Minor, spreading then to the entire empire. Territory was organized into administrative and military units, the themata, in which both civil and military powers were concentrated in the hands of one military commander. Soldiers were from then on recruited among the free peasant smallholders, who offered their military service in exchange for land that enjoyed certain privileges.

Disaster as a rule breeds the need for reform and in the Byzantine empire this was not only expressed in terms of administration. The movement of Iconoclasm (literally icon-breaking) has its roots in the traumatic experience of the seventh century. It does not need to concern us here when exactly it began – was the eruption of the volcano at Thera/Santorini in 726 an omen suggesting divine wrath? Surely the Arabic juggernaut must have seemed reason enough for this divine displeasure. And the Arabs did forbid figurative art. A sober look at this development would look like this: from the early-to-mid-eighth century Byzantine emperors had religious images removed and later destroyed. Their main motive must have been to counteract the excessive veneration of images which came close to idolatry – surely this could have been a reason why the infidels were winning and God’s chosen people were being chastised by one defeat after another. Persecution of those opposing these measures, mainly monks, varied, but some of the most fervent supporters of icons were executed.

Iconoclasm was reversed by an empress: the widowed Irene (r. 780-802), acting as a regent for her young son, summoned a council in 787 (the seventh and last ecumenical one) in Nicaea, which condemned it and restored the veneration of images, while in the process destroying pretty much all that their adversaries had ever written and thus making it very difficult for us to view the events in a balanced way.

![]()

Iconoclasm coincided with the successes of Constantine V (r. 741-775) in both Asia Minor and the Balkans. However, after Irene, the empire suffered a series of setbacks that led to a second phase of Iconoclasm that began in 815 and ended in 843. Again, an empress acting as regent, Theodora (r. 842-55), restored the images in what is still today celebrated as the ‘Triumph of Orthodoxy’. At the end of Iconoclasm, Christian art had prevailed and became an essential aspect of worship.

On Christmas Day 800, during the reign of Irene as empress, the coronation of Charlemagne, ruler of a western empire controlling France, the Rhineland and Northern Italy, in Rome gave the world a second Roman emperor. Despite the fact that Charlemagne’s state did not enjoy a long life, the ideological antagonism from the West would become a recurrent phenomenon in the centuries to come.

After 843 the empire began a period of revival that lasted for two centuries and marked a long phase of territorial expansion, political and cultural radiance over its neighbours and a flourishing of education and the arts. Gradually, imperial authority was restored in the Balkans and parts of Syria and Asia Minor were reconquered. In what is perhaps the most enduring consequence of Byzantine policy, a number of Slavic states embraced Christianity coming from Constantinople (not without fierce competition with Rome). Byzantine missionaries developed the first Slavic alphabet and the newly converted were allowed to use it in their services. These were the early steps in creating what was termed a ‘Byzantine Commonwealth’.

With the state expanding and the economy growing, a cultural revival developed as well. It was marked by an effort at collecting and systematizing knowledge by compiling vast encyclopaedias with the most varied contents: ancient epigrams, lives of saints, dictionaries, medical and veterinary texts, practical agricultural wisdom and military treatises, as well as thematically organized volumes on embassies or hunting. The central figure in this revival (perhaps more as a result of imperial propaganda than of actual contribution) was the learned emperor Constantine VII (944-959) under whose auspices a number of works were created dealing with the imperial ceremonies, the administrative division of the empire and a secret manual of governance addressed to his son. This revival of learning was a direct result of the important scholars produced by the fostering of education from the ninth century. Classical Antiquity, no longer carrying the negative connotation of paganism, was studied and copied.

The economic and political stimulus behind the revival, however, fuelled some rather untoward trends as well. The military aristocracy gained more and more power, and, in its quest for more land, started to encroach on the villages and their free peasants, potentially stripping the state of tax revenues and the army of its manpower. The emperors legislated against this and civil wars ensued. It took as resolute an emperor as Basil II (r. 976-1025) to crush those military clans, but his victory was short-lived. Following the general and growing disarray that ensued after his death, the aristocracy made a decisive comeback in the person of Alexius I Comnenus (r. 1081-1118).

When he took over the reins of the empire he faced a very different political situation from that which had existed less than half a century before him. The Seljuk Turks had started conquering Asia Minor, the empire’s heartland. Moreover, the Normans had taken over large parts of Italy and then attacked the empire in the Balkans, while Venice, aided by commercial privileges accorded to it by Byzantium, was branching out in the eastern Mediterranean. Finally, the papacy’s zeal for reform was changing it into a formidable power able to stand above secular rulers. Certainly the schism between Rome and Constantinople that had occurred in 1054 was not a positive development, although it was hardly surprising given the troubled history of antagonism between the two sees.

The crusades should also be seen in this context of Western expansion. Under the first three Comnenian emperors (roughly until 1180) Byzantium managed to escape the onslaught of the crusaders largely unscathed (and even partially to use them to its advantage in Syria and Asia Minor). Towards the close of the twelfth century the relationship with the West deteriorated. The tragic endpoint of this process was the capture and looting of Constantinople by the French and Venetian armies of the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

The fragmentation of the once centralized empire was a blow from which it never fully recovered. Constantinople itself was governed by the Latins for some sixty years, and a number of Latin and Greek states of varying size and importance were established in Greece and Asia Minor. From this period onwards, the interaction with the West became the dominant theme in Byzantine affairs. Both cultures came much closer to each other and a true exchange took place – not always favoured by the Byzantines. After 1204 a great number of artefacts of the highest quality wandered to the West, but not many of them have survived until today (for example, the relics from Constantinople that were housed in the Sainte Chapelle in Paris were destroyed in the 1789 Revolution).

In 1261 Constantinople was recaptured and a new dynasty, the Palaeologoi, gained power and held on to it for the last two centuries of the empire’s existence. But ‘empire’ was now hardly the right designation for this state. From the very beginning it was engaged in a fight for survival against foreign forces and internal frictions. A civil war that began in 1341 functioned as a watershed for the fate of the state. Until that time the empire had weathered its problems with difficulty, but still preserved an international importance. It is unfortunate that the civil war ended only a few months before the outbreak of the Black Death in 1347. There was no time for recovery, with both Ottoman Turks and Serbs expanding at the empire’s expense. The last century saw the empire in constant decline, although some Byzantines profited from the decentralization of power and the massive influx of Italian merchant capital into the Levant.

In the face of danger, opposing factions emerged dynamically. On the one side were people who looked to the West for help; there were conversions to Catholicism and for the first time after many centuries the translation and study of works in Latin. Ending the Schism was seen by those pro-Western advocates as the only solution. Many of the emperors pursued this policy right to the very end, when John VIII (r. 1425-1448) took part at the Council of Ferrara-Florence in 1438-39. But the movement of knowledge functioned the other way around as well; Greek scholars travelled to Italy taught Greek to enthusiastic audiences and brought with them manuscripts containing texts long forgotten in the West – Plato, above all. There, these texts were translated into Latin and certainly made an important contribution to humanism and gave impetus to the Renaissance.

Yet there was a different Byzantine reaction at the same time, inward-looking amidst the imminent disaster. This was focused on tradition and Orthodoxy; it rejected union with the Roman church and feared that the Latins would undermine their Byzantine identity. The gap would not be bridged. Perhaps not surprisingly, the Palaeologan period saw a remarkable flourishing of literature and art, both in response to Western impulses and in keeping with Byzantine traditions. Ancient texts were studied, meticulously edited and commented on by large numbers of intellectuals who enjoyed patronage. Brilliant monuments of the period survive, such as the church of the Chora Monastery and the Virgin Pammakaristos in Constantinople.

As the state became weaker, the church was swiftly becoming the only reliable institution. ‘A church we have, an emperor we don’t,’ claimed Basil I, the prince of Moscow, only to be strongly rebuked by the patriarch: ‘It is impossible for Christians to have a church and no empire.’ Yet this is what happened after 1453 when the young Mehmed II accomplished what a number of his predecessors had failed, the capture of Constantinople, the City (Greek: polis) par excellence and the colloquial phrase eis tin polin (to the city) became the name of Istanbul.

Dionysios Stathakopoulos is Lecturer in Late Antique and Byzantine Studies at King's College London. This article first appeared in the November 2008 issue of History Today.