A Short History of Sushi

The ancient origin of sushi, the Japanese dish of humble beginnings that conquered the world.

On the morning of 5 January 2019, gasps of amazement rippled through Tokyo’s cavernous fish market. In the first auction of the new year, Kiyoshi Kimura – the portly owner of a well-known chain of sushi restaurants – had paid a record ¥333.6 million (£2.5 million) for a 278kg bluefin tuna. Even he thought the price was exorbitant. A bluefin tuna that size would have normally cost him around ¥2.7 million (£18,700). At New Year, that could rise to around ¥40 million (£279,000). Back in 2013, he’d paid no less than ¥155.4 million (£1.09 million) for a 222kg specimen: a lot, to be sure. But still a lot less than what he’d just paid.

Tasty and fresh

It was worth paying over the odds, though. It was, by any standards, a beautiful fish – ‘so tasty and fresh’, as a beaming Mr Kimura told the world’s press. It was also a rarity. Though not as critically endangered as its southern relatives, the Pacific bluefin tuna is classified as a vulnerable species and, over the past six years, efforts have been made to limit the size of catches. Most of all, it was great advertising. By paying such a colossally high price for a tuna, Kimura was telling the world that, at his restaurants, the sushi is made from only the very best fish.

It was a dazzling – even ostentatious – demonstration of how greatly sushi is prized in Japan. When it comes to those tiny mounds of vinegary rice, topped with delicate slivers of seafood, almost any price is worth paying. Sushi is not simply a meal to be eaten, but a dish to be savoured. As the celebrity chef Nobu Matsuhisa has recently pointed out, it is ‘an art’ in itself. Some would go even further. For many people, it is the acme not just of Japanese cuisine, but of Japanese culture. Reserved for the most special occasions, it is bound up in the popular imagination with ideas of sophistication and good taste.

There is, perhaps, some irony in this. Sushi was, at first, neither sophisticated nor even Japanese.

Though the evidence for its early history is rather sketchy, it seems to have begun life at some point between the fifth and the third centuries BC in the paddy fields alongside the Mekong river, which runs through modern Laos, Thailand and Vietnam. Then, as now, the shallow waters were the perfect home for aquatic life, especially carp, and farmers often went fishing to supplement their meagre diets. But this posed a problem. Whenever a catch was landed, most of the fish would go off in the heat before they could be eaten. In order to avoid wasting food, some method of slowing, or at least controlling, the decay was needed. Thankfully, the glutinous rice grown in the surrounding fields turned out to be the perfect preservative. First, the fish were gutted, rubbed with salt and placed in a barrel to dry for a few weeks. Then the salt was scraped off and the bellies of the fish packed with rice before being placed into wooden barrels, weighed down with a heavy stone, and left to rest. After several months – sometimes up to a year – anaerobic fermentation would begin, converting the sugars in the rice into acids and thus preventing the microorganisms responsible for putrefaction from spoiling the flesh. Whenever there was a need, the barrel could then be opened, the rice scraped off and the remaining fish eaten. The smell was, of course, revolting; but the taste was delicious, if rather bitter. Best of all, nothing was wasted.

Gradually, this rudimentary form of sushi – known as nare-sushi – began to spread. From the Mekong it made its way south towards Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines and north, along the Yangtze and into the Yunnan, Guanxi and Guizhou provinces of modern China. Invasion took it further. Following the conquest of the Yeland, Dian and Nanyue tribes by the Han people in the second century BC, a process of cultural assimilation then brought nare-sushi into the Chinese heartlands. For many years it remained a ‘poor’ food, favoured by those who, like its first consumers, worked in or near paddy fields. But, in time, it became so widely eaten that it gained acceptance in more elevated sections of society, as well – so much so that it was even mentioned in the earliest surviving Chinese encyclopedia, the Erya.

Revulsion and innovation

Eventually, nare-sushi reached Japan. It is not known exactly when it arrived, but the earliest reference to it appears in the Yōrō Code, a legal code compiled in 718, during the reign of the Empress Genshō. Its reception was, admittedly, rather mixed. A story from the Konjaku Monogatarishū (Anthology of Tales from the Past), written in the early 12th century, left no doubt that, while it tasted good, many Japanese found its smell repellent.

Revulsion was, however, to prove a spur to innovation. During the early Muromachi period (1338-1573), steps were taken to make sushi more palatable. Rather than leave the fish in barrels for months – or even years – at a time, the fermentation process was reduced to a few weeks. This meant that less acid was allowed to form and the stench was kept to a minimum.

Recipes from the Historian’s Cookbook: An Early American Take on Sushi

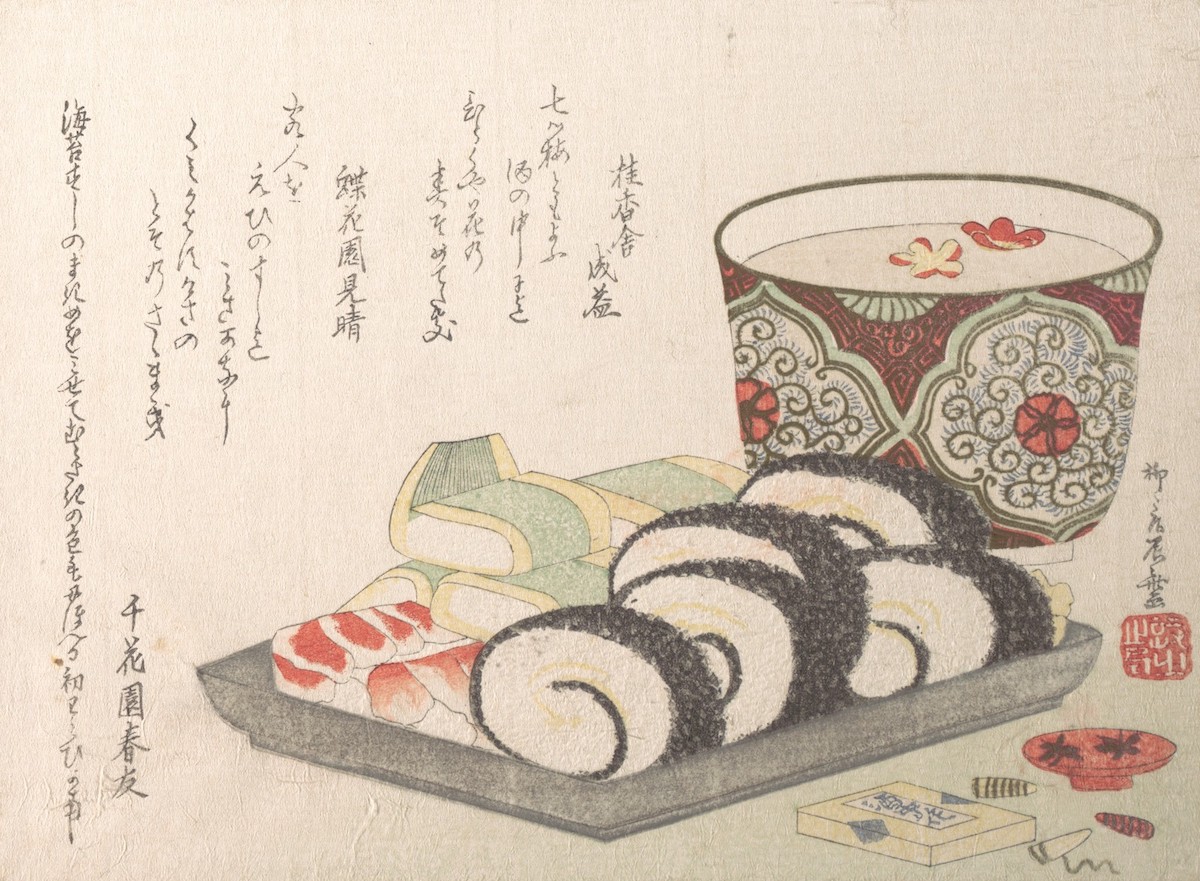

But this also had the effect of making the contents of the barrel rather less sour. Instead of being mouth-puckeringly bitter, the rice was now pleasantly tart and could be eaten with the fish instead of simply being thrown away. It was just the sort of flavour the Japanese were looking for. During the 12th century, the development of rice vinegar had transformed tastes and created an appetite for acetic foods. All sorts of new dishes had been developed, including namasu (vegetables in vinegar) and tsukemono (pickles). But none was quite as popular as this new combination of semi-fermented fish and rice – known as han-nare. No longer the preserve of the rural poor, it was soon being enjoyed by artisans, merchants, warriors and, eventually, even nobles.

Fast sushi

Now that the fermentation had been cut down, it was not long before someone started to wonder whether it was necessary at all. Although it had fulfilled a valuable function on the banks of the Mekong and the Yangtze, its utility was less obvious in Japan. Not only were salt-water fish more readily available, but the growth of prosperity, the acceleration of urbanisation and improvements in domestic trade had made long-term preservation less of a concern.

By the middle of the 17th century this had led to the emergence of a third form of sushi. Known as haya-zushi (fast sushi), this did away with fermentation altogether, while preserving the dish’s familiar tart flavour. Instead of waiting for the sugars in the rice to be turned naturally into acids, vinegar was simply added instead. It was then packed into a box, under slices of cooked or cured fish, and pressed with a heavy weight for no more than a couple of days. Over time, different prefectures added their own twists to this, either to reflect regional tastes or to take account of the availability of different ingredients. In Toyama, for example, the sushi was wrapped in bamboo leaves, while in Nara persimmon leaves were used.

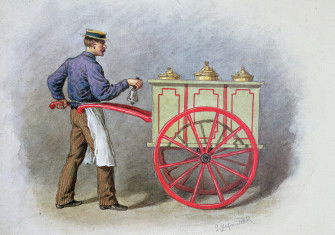

If you were going to do away with fermentation, however, why not get rid of pressing, as well? After all, its purpose had only ever been to prevent air getting to the fish while the sugars in the rice turned to acid. Now, it was just a hang-over from the past: aesthetically pleasing, perhaps, but wholly unnecessary. Besides, it slowed preparation down and, by the early 19th century, time was money in Japan’s growing cities. Busy rushing here and there, people needed something quick and easy to eat – not something which took days to make.

To meet this need, a fourth form of sushi was developed. Consisting of slices of cooked or cured fish laid over vinegar-seasoned rice, this was similar to modern nigrizushi. What distinguished it, however, was its size. Each piece was two or three times bigger than the bite-sized treats we are used to eating today. The fish was treated rather differently, too. Before being served, each slice was carefully steeped in vinegar or soy sauce, or else coated in a thick layer of salt, so as to ensure a consistency of taste – and to ensure that it kept fresh for at least a while.

Known as Edo-mae, this sushi was named for the city of Edo (Tokyo), where it was developed in the 1820s or 1830s. According to one popular legend, it was invented by a chef named Hanaya Yohei (1799-1858) at his stall in the north-east of the metropolis in around 1824. Whatever the truth of its origins, its huge popularity led to the establishment of the first sushi emporia. Apart from Yohei’s restaurant, the most famous were Kanukizushi and Matsunozushi (which still exists); and within a few decades, they numbered in the hundreds, if not thousands. Indeed, if one mid-century encyclopaedist is to be believed, every hectare of Edo contained at least one sushi stall.

Edo-mae was not to remain the preserve of Edo for long, though. In 1923, the Great Kanto earthquake – which killed more than 100,000 people and left many more homeless – forced several sushi chefs from the city and thereby helped to spread the new sushi throughout Japan.

Fridge magnet

It was, however, technology which created the sushi we know today. With the development of refrigeration, it became possible to use slices of raw fish for the first time. Other types of fish also came into vogue. Whereas fatty fish like tuna had previously been dismissed, because there had never been a suitable method of curing or cooking them, they could now be served fresh whenever needed. Coupled with the persistent image of refrigerators as ‘luxury’ items, this greater variety transformed sushi into a ‘festive’ food; a refined treat to be enjoyed with family and friends on special occasions.

Yet, even as it was being enshrined as the pinnacle of Japanese culture, it was spreading its wings further. After the Second World War, the US occupation and the growing ease of international travel took it across the Pacific and beyond. In the 1960s, Californians even pioneered their own form of sushi – the inside-out roll. Since then, ever more inventive variations have been introduced the world over.

So, if it’s worth Mr Kimura paying a king’s ransom for a single bluefin tuna, it’s worth keeping the humble origins of this most ‘regal’ of dishes in mind. Since its emergence more than 2,000 years ago sushi has changed almost beyond recognition. If its transformation from a sticky, stinky leftover to a fragrant delicacy shows anything, it is that it will probably go on changing for years to come.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book is Humanism and Empire: The Imperial Ideal in Fourteenth-Century Italy (Oxford, 2018).