In Focus: St Pancras Rises

A photograph of 1867 which shows the construction of one of the glories of Victorian architecture.

As the Second Reform Bill found its way onto the statute book in 1867, feelings in Britain were mixed. There was both apprehension and excitement, since this giant step towards full-blown democracy could also be seen as a threat to continuity and tradition. The perfect symbol of these conflicting emotions was the railway terminus and accompanying hotel under construction for the Midland Railway at St Pancras in London. George Gilbert Scott’s hotel, which forms the façade, is one of the supreme efforts of Victorian Gothic architecture. Behind it, the train shed is a manifestation of Victorian engineering at its most daring and innovative.

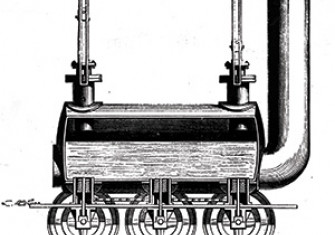

This photograph of 1867 shows the beginnings of the basement, the secret behind the single-span structure, then the largest in the world, that M.H. Barlow devised to house the railway’s platforms. The Regent’s Canal ran immediately to the north and Barlow did not want to put his lines into a tunnel underneath it because that would have faced engines with a steep incline almost immediately on leaving the station, without having gathered speed. So a bridge was to carry them over the canal, meaning that the platforms would be well above ground level. Barlow realised that the girders supporting the station floor could act as a series of trusses, to anchor a huge arched roof crossing all the platforms in one leap. There was no need for pillars to clutter up the space or for a spine wall down the middle to accommodate a central line of supports, something Barlow wanted to avoid, since the Midland had a tunnel underneath St Pancras linking its lines to those of the Metropolitan Underground and so to the markets for Midlands coal in South London and beyond. The basement’s 800 uniform cast-iron columns supporting the station floor from below were placed 14 feet apart, a spacing dictated by the dimensions of the beer barrels from the breweries of Burton-on-Trent, which were to be stored there before slaking London’s thirst. There was a lift to lower wagonloads of barrels onto rails running down the centre of the basement.

The stubs of the series of arches made by the BIC of Derby to support the roof can be seen on the left and some columns towards the back. The cartload of coal is probably fuel for the steam cranes and shovels employed on the site. In the background the gasometers can be discerned, one of which has been lovingly dismantled, conserved and then re-erected as part of today’s King’s Cross redevelopment. The nearly 250-ft wide train shed was not the Midland’s only claim to fame: it also pioneered third-class carriages, upholstered seats for all and the serving of meals on trains, though its reputation for punctuality fell below that of its rivals.

After he had completed his building, Scott admitted ‘it is possibly too good for its purpose, but having been disappointed, through Lord Palmerston, of my ardent hope of carrying out my style in the Government offices [in Whitehall] … I was glad to erect one building in that style in London’. A wag, agreeing with him, said: ‘C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la gare’, which indeed it is not; it is a hotel. But since the refurbishment of the train shed and the arrival there of Eurostar in 2007, it truly can be called a magnificent railway station, rescued from decades of neglect. On the escalator from the basement to the platforms, spirits as well as body and luggage are uplifted as it comes into view.