The Death of Tamerlane

Tamerlane, or Timur, one of history's most brutal butchers, died on 18 February 1405.

In January the Scourge of God caught a cold. One of history’s most brutal butchers, now perhaps in his seventies, had set out with an army 200,000 strong from Samarqand, his capital, to try conclusions with the Chinese Empire, 3,000 miles away. It was a freezing cold winter, with the country deep in snow and the rivers frozen solid, and the army halted at Otrar in what is now Kazakhstan. The doctors’ efforts to cure their master, which included packing him in ice as the cold turned to fever, failed and it became clear that he was dying. Eventually, surrounded by his women and senior commanders, in a weak, almost inaudible voice he made an eloquent speech, telling them not to weep or run about madly tearing their clothes but to pray to God to have mercy on him.

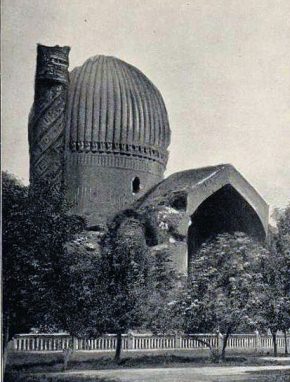

He died at about eight o’clock in the evening, while icy winds howled round the palace and the tents of his army outside. The Chinese expedition was abandoned and the body was taken back to Samarqand to be interred beneath the dome of the Gur Amir mausoleum in a steel coffin under a slab of black jade six feet long, which was then the largest piece of the stone in the world. An inscription records: ‘This is the resting place of the illustrious and merciful monarch, the most great Sultan, the most mighty warrior, Lord Timur, Conqueror of the World.’

In Europe the name Timur iLeng, Timur the Lame, became Tamerlane or Tamburlaine. Lame he was, mighty he was, merciful he was not. As his latest biographer Justin Marozzi says, the millions he slaughtered – ‘buried alive, cemented into walls, massacred on the battlefield, sliced in two at the waist, trampled to death by horses, beheaded, hanged’ – would have had a different opinion. Of Mongol ancestry from what is now Uzbekistan, he began as a sheep-rustler and bandit, and was injured in a skirmish which left him lame in his right leg and unable to raise his right arm. In 1941 his tomb was opened by a Soviet archaeologist, Mikhail Gerasimov, who confirmed the injuries.

Building up a force of several hundred horsemen, Timur took service under an invading Mongol chieftain, seized Samarqand, took a wife descended from Genghis Khan and went on to an astonishing career of conquest until he ruled from Damascus to Delhi. Efficiently organised armies under his horse-tail standard covered immense distances. He destroyed the Golden Horde, conquered Persia and Mesopotamia, invaded Russia, Georgia, India, Syria and Turkey. Thousands of women were carried off as slaves. At Baghdad he had 90,000 of the inhabitants beheaded so that he could build towers with their skulls. At Sivas in Turkey, where he promised no bloodshed in return for surrender, he had 3,000 prisoners buried alive and pointed out that he had kept to the letter of his oath. His atrocities were intended to strike terror into the hearts of opponents, and cities which surrendered promptly were sometimes spared a sack. He was a Muslim and he justified his campaigns against Christians and Hindus as spreading the true faith, while when he attacked and slaughtered fellow-Muslims, as he very frequently did, they were always described as ‘bad Muslims’. Timur was a patron of art and learning and he turned Samarqand into an exquisitely beautiful city. His empire, which was never more than the expression of his personal dominance, did not survive his death.