Lenten Fare

Gillian Goodwin on traditional recipes for Lent.

'... Thou didest eate nothinge but symnels, honny & oyle: marvelous goodly wast thou & beutifull, yee even a very Quene wast thou...'. The Lord shows Jerusalem her abominations through the mouth of the prophet Ezekiel in Miles Coverdale's 1535 translation of the Bible.

Bishop Coverdale's tone shows that simnels were special, a quality product, whereas the 'fine flour' of the King James' Bible and more recent translations is much less telling.

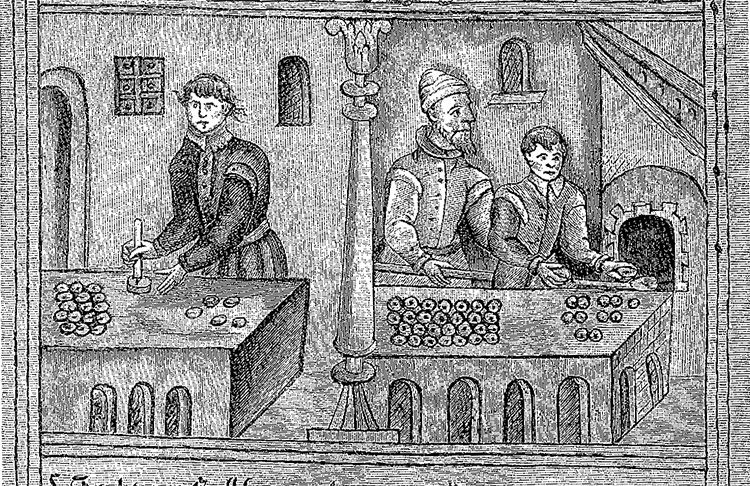

Simnels were indeed made from the finest white flour, coarser than it would be today because bolters (or sifters) were made of cloth but, given honest millers and bakers, without present-day extractions and additives. By 1535 simnels had been around a long time: thirteenth-century Fleta's account of the regulations of bread mentions them; bakers were allowed to charge more for them because they had to be cooked twice, 'quia bis coctus erit'. The dough was boiled or scalded (the French called them eschaudez) and then baked in the oven. The phrase 'well sodden and well baked' occurs frequently in the York bakers' 'booke'.