Original Pirate Material

On 28 March 1964, Radio Caroline hit the waves. How did pirate radio discover its winning formula and what happened next?

A Dutch navy boat pulls up alongside the Radio Caroline transmitter ship Mi Amigo, c. 1973. National Archives (CC0).

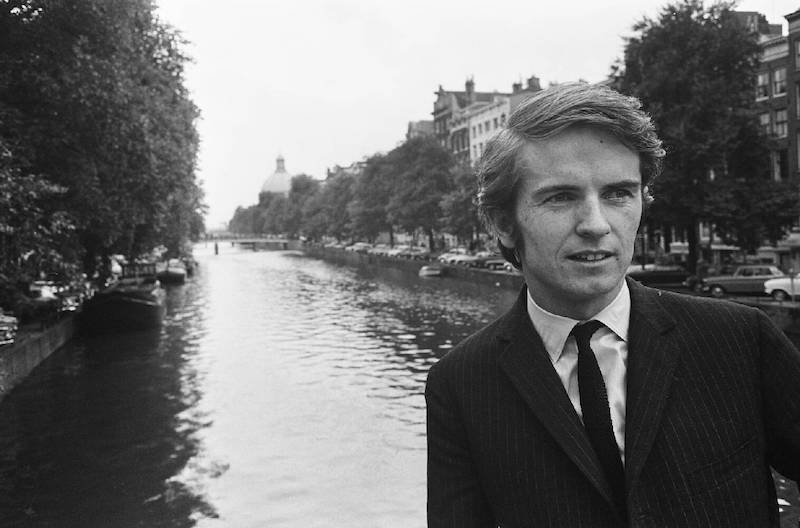

Shortly before midday on Easter Saturday 28 March 1964, the first medium wave broadcasts were heard from the offshore pirate station Radio Caroline. Based on a converted ferry moored just outside UK territorial waters, Radio Caroline was the brainchild of Dublin-born Ronan O’Rahilly. His father Aodogán owned the port of Greenore in County Louth and it was there that Ronan was able to get his radio ship fitted out in relative secrecy.

Radio Caroline’s conception was predominantly a response to the BBC’s limited pop music output, in particular its restricted needle time – the amount of recorded music it could play in any one day. The broadcaster’s pop coverage was largely governed by its relationship with the Musicians’ Union and the various copyright and licensing revenue organisations, including the Performing Rights Society and the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society, all of which mitigated against any practical expansion in the Light Programme’s pop output, a national radio station launched in 1945 which was the forerunner to Radio Two. By the time O’Rahilly established his radio station Britain had a thriving beat music scene and the Merseybeat era, galvanised by the phenomenal success of the Beatles and other Liverpool-based groups, was arguably at its peak. With a plethora of other UK beat groups beginning to dominate the Top 30, British pop music was changing rapidly, a situation with which the Light Programme with its pop orchestras, often playing cover versions of the hits of the day, was ill-equipped to keep pace.

Radio Caroline was not the first European radio station to circumvent legislation by mooring a vessel in international waters. Radio Mercur (Denmark, 1958-62), Radio Nord (Sweden, 1960-62) and Radio Veronica (the Netherlands, 1960-74) were the earliest of seven continental pirates that preceded Caroline. O’Rahilly’s station was not even the first British-based offshore initiative. Allan Crawford’s Project Atlanta had been planned since 1960. The two briefly shared a mooring facility in Greenore harbour and Caroline narrowly beat Atlanta to the airwaves by a few weeks. The two stations merged into Radio Caroline North and South to ensure nationwide coverage. Although several other pirate stations launched over the next three years it is Radio Caroline, along with the equally successful Radio London, which began broadcasting in December 1964, that have become largely synonymous with the offshore radio era.

The received wisdom about pirate stations is that they played a non-stop selection of Top 40 records 24 hours a day from the start. Analysis of those earliest broadcasts from Radio Caroline in March and April 1964 shows that this was far from the truth. The station played the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and other beat groups of the period, but it also featured artists as varied as Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Ella Fitzgerald, Ray Connif, Mantovani and The Mike Sammes Singers, as well as showtunes from musicals by Judy Garland and Stanley Holloway. In its first few months, the output of Radio Caroline resembled a kind of hip easy listening version of the Light Programme.

This was due in no small part to the station’s cultural milieu, which closely reflected its ‘Kings Road Chelsea Set’ origins. One of Caroline’s chief backers was Jocelyn Stevens, at that time editor-in-chief of Queen magazine. By the early 1960s Stevens had transformed Queen from a poor imitation of Tatler into a stylish publication. From 1962 Queen carried the Top 10 playlist of the recently opened Annabel’s Nightclub in Berkeley Square. These lists, with their emphasis on jazz, bore a marked similarity to the records that were regularly aired on Caroline in those earliest broadcasts.

The most prominent of Radio Caroline’s original financial backers was the Eton- and Cambridge-educated entrepreneur John Sheffield, founder and chairman of the Norcros group of companies, but also among the initial list of signatories and small investors were a number of long-term Chelsea residents. As O’Rahilly put it in Channel 4’s The Black and White Pirate Show, aired on 13 July 1987: ‘Without the capitalist pigs of the City of London there would have been no Caroline.’ To this assertion he might have added Cadogan Square and Paulton Square dowagers, plus a discreet number of philanthropic heiresses, lords and earls. It is a distinctive aspect of the ‘long 1960s’ (which began with the formation of a new bohemian upper middle class of the 1920s) that so many Swinging London initiatives were launched on a mixture of old money, creative whims, trust fund wealth and the emerging micro-economies of the newly affluent young.

Chelsea’s unique social and cultural blend was one of the main influences in moulding Caroline’s distinctive rebellious image in the 1960s. It certainly offers a contrasting economic model to that of its main offshore rival Radio London, also known as ‘Big L’. Created by a Texan businessman and with a number of high-level investors, ‘Big L’ boasted a professional programming and sales team; it was to all intents and purposes a successful commercial radio station that just happened to be based on a ship. It even enjoyed a better broadcasting signal. Its streamlined UK version of American Top 40 radio was immediately a hit with listeners and it was chiefly in response to this success that Caroline finally dropped the more broad-based element of its music policy and moved over to a solid output of pop and rhythm and blues.

Radio London provided the majority of DJs when the BBC was recruiting for the launch of Radio One in September 1967. ‘Radio London had its act together and was much better organised, whereas Caroline kind of reflected O’Rahilly’s attitude to life’, record company promoter Tony Hall told me when I interviewed him in 1988. This much was confirmed when Radio Caroline, alone among the offshore stations, chose to continue broadcasting when the Marine Broadcasting Offences Act was brought in on 14 August 1967, a piece of legislation which outlawed the pirates. Legislation had been inevitable for some time. The draft Bill to outlaw the pirates proposed to make it illegal for any British citizen or company to work for, advertise on or otherwise supply, assist or fund an offshore station. It was published on 2 July 1966, over a year before it came into force, and received its first reading in the House of Commons on 27 July. On 20 December 1966 the government issued its White Paper on the future of broadcasting and recommended for the first time that the BBC set up a dedicated pop music service to replace the pirate stations.

By this time Radio Caroline, the sole survivor of the offshore radio era, had moved its entire operation to Amsterdam. The Dutch did not at that point have equivalent anti-pirate legislation and the Netherlands’ own offshore pirate Radio Veronica was still broadcasting. ‘Listen, all the others are only in it for the money’, O’Rahilly told Caroline programme director Tom Lodge when that legislation was being drafted. ‘We are in it for a principle. We are in it for an ideal. We are in it for a philosophy.’

That philosophy, reflecting the spirit of the times but economically reckless, saw money squandered on a huge scale at the station. Even at its height Caroline could never compete with the advertising revenue grossed by Radio London. ‘Big L’ had a shrewd business plan and recruited accordingly, bringing in the corporate expertise of the J. Walter Thomson agency to oversee its sales team. Caroline was always more cavalier in the way it did business. A comparative fiscal model of flawed ‘hip capitalism’ in the second half of the 1960s was the Beatles’ Apple venture, a multimedia corporation conceived to enable members of the band to invest in business opportunities (and to find tax shelters for their capital), floated on similarly high ideals but which floundered and failed when faced with economic reality.

Everybody involved in the creation of Caroline admits that had a navy gun boat pulled up alongside their vessel in the first weeks of broadcasting the entire dream would have been scuppered. Instead, with radical objectives the pop pirates thrived for three and a half years, broadcasting 24 hours a day from the coastal waters of England. Sixty years later, Radio Caroline lives on as a licensed UK broadcaster.

Rob Chapman is a music biographer and a cultural historian. He is the author of Selling the Sixties: The Pirates and Pop Music Radio (Routledge, 1992).