Past Precedents for Muslim and Jewish Peace

A solution to the conflict between Israel and Palestine seems as far away as ever. But, says Martin Gilbert, past relations between Muslims and Jews have often been harmonious and can be so again.

Enmity between Jews and Muslims seems to be a fact of life in the 21st century: a hostility that impinges on Jewish and Muslim life worldwide and, in particular, on the Arab-Israeli conflict, now in its sixth decade. When did this enmity begin? How was it sustained? Why did it survive? In order to answer these questions we must look to the other side of the coin, to a story that might serve both sides today as a positive reminder of what could lie ahead.

Enmity between Jews and Muslims seems to be a fact of life in the 21st century: a hostility that impinges on Jewish and Muslim life worldwide and, in particular, on the Arab-Israeli conflict, now in its sixth decade. When did this enmity begin? How was it sustained? Why did it survive? In order to answer these questions we must look to the other side of the coin, to a story that might serve both sides today as a positive reminder of what could lie ahead.

Hostility has unquestionably been a part of the long historical narrative of Arab-Jewish relations. Among the chants and placards that accompanied and followed the Turkish ships carrying aid to the Gaza Strip, and which were intercepted by Israeli forces, was the Muslim rallying cry: ‘Jews: remember Khaibar. The army of Muhammad is coming back to defeat you.’

This cry has echoed in each decade of modern times. On August 7th, 2003, when Amrozi bin Nurhasin, one of the ‘Bali bombers’, entered an Indonesian courtroom for sentencing, having been found guilty of blowing up more than 200 people – none of them Jews – he shouted out the same rallying cry in the presence of the world’s media.

The cry refers to an event that took place in the year 628, when, as leader of the new faith of Islam, the Prophet Muhammad achieved one of his first military victories, against a Jewish tribe living in the oasis of Khaibar on the Arabian peninsula. Contemporary Arab sources report that between 600 and 900 Jews were killed in the battle. This Muslim victory was followed by the spread of segregation and taxation for non-Muslims, as well as forcible conversion to Islam.

Two months after Amrozi bin Nurhasin received his sentence of death, the Malaysian Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamad – who in 1986 had inaugurated an ‘Anti-Jews Day’ – told the Tenth Islamic Summit Conference held in the Malaysian city of Putrajaya, that: ‘1.3 billion Muslims cannot be defeated by a few million Jews. There must be a way … Surely the 23 years’ struggle of the Prophet can provide us with some guidance as to what we can and should do.’

Within three years of this appeal, Palestinian Arab voters cast a majority of their votes for Hamas, the Islamic Resistance Movement (44 per cent as against the 41 per cent who voted for Hamas’s nearest rival, Fatah). The Hamas Charter, promulgated in 1988, looks forward to the implementation of ‘Allah’s promise’, however long it might take:

The Prophet, prayer and peace be upon him, said:

‘The Day of Judgement will not come about until Muslims fight the Jews (killing the Jews), when the Jew will hide behind stones and trees. The stones and trees will say O Muslims, O Abdullah, there is a Jew behind me, come and kill him.’

From the time of the Babylonian conquest of Judaea 2,500 years ago Jews have been dispersed, first in Mesopotamia and Persia (now, respectively, Iraq and Iran), then, following the Roman conquest of Judaea, throughout Arabia and North Africa from Egypt to Morocco: all lands that came under Muslim rule with the conquests of Muhammad. In the 12th century, 600 years after the death of Muhammad, the Jewish sage Maimonides (1135-1204) described the situation of the Jews after five centuries of Muslim rule: ‘No nation has ever done more harm to Israel.’ He went on to elaborate: ‘None has matched it in debasing and humiliating us. None has been able to reduce us as they have.’

Reflections on the past

Yet there is another side to this tale of debasement and humiliation. By the end of the 20th century Bernard Lewis, among the most eminent historians of the Middle East, a lifelong student of Jews and Islam and himself a Jew, reflected on the 14 centuries of Jewish life under Islamic rule since Muhammad. He concluded that the situation of Jews living under Islamic rulers ‘was never as bad as in Christendom at its worst’, even if it was never ‘as good as in Christendom at its best’. Lewis continued: ‘There is nothing in Islamic history to parallel the Spanish expulsion and Inquisition, the Russian pogroms, or the Nazi Holocaust.’

From the time of Muhammad in the seventh century and the rapid military conquests of Islam that followed the Jews were subjects of their Muslim rulers throughout a great swathe of land, stretching from the Atlantic coast of Morocco to the mountains of Afghanistan. Being non-Muslims, the Jews held, along with all Christians and other religious minorities under Muslim rule, the status of dhimmi, literally the ‘people of the contract’ or ‘people of the book’, referring to the common roots of the Abrahamic religions. Dhimmi were of an inferior status which, while giving them protection as a minority to worship in their own faiths, subjected them to many vexatious and humiliating restrictions in their daily lives, including a sometimes punitive jizya, or head tax.

History shows, however, that in every century and in every land under Muslim rule, despite moments of persecution, dhimmi regulations could be relaxed, the jizya reduced to a nominal amount with the Jews thus becoming an integral and respected part of Muslim society. This accommodation has a long history. In 638, under the second Caliph, Muhammad’s companion and second father-in-law Omar ibn al-Khattab (r. 634-44), the army of Islam conquered several cities formerly under Christian rule in which the Jews openly aided the Muslim conquerors, hoping to be free of Christian persecution. Jewish soldiers fought in the Muslim ranks as volunteers, Jews acted as guides and provided food and provisions for the Muslim armies.

A new Jerusalem

When Omar made his way to Jerusalem in 638 the Jews asked him for permission for 200 Jewish families to live in the city. Because the Christian patriarch vehemently opposed this suggestion, Omar fixed their number at 70. Omar gave these Jewish families their own area in Jerusalem, located in what is now the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. There they were allowed to build a religious college and a synagogue and to pray in the neighbourhood of the Temple Mount, once the site of Solomon’s Temple.

Contemporary Jewish sources emanating from Baghdad relate that when Omar conquered Babylonia he confirmed that the leader of the Jewish community there – who was known as the Exilarch and was at that time Bustanai ben Haninai – would remain as Exilarch under Muslim rule, with authority over the Jews of the province (modern-day Iraq).

Sixty years later, another Caliph, Abd al-Malik, appointed Jewish families to be guardians of the Temple Mount – known to Muslims as Haram ash-Sharif (‘The Noble Sanctuary’) – and charged them with maintaining the cleanliness of the Mount and with making glass vessels for its lights and kindling them. He also decreed that these particular Jews should be exempt from payment of the jizya. Other Jews obtained positions of authority in al-Malik’s administration.

Jewish doctors, merchants and artisans lived prosperously and worked productively under Muslim rule. In Afghanistan, in the 11th and 12th centuries, Jewish communities likewise flourished; Sultan Mahmud (998-1030) assigned a Jew named Isaac to administer his lead mines and melt ore for him. One of the most successful Jews in a Muslim land in the 12th century was Abu al-Munajja Solomon ben Shaya, a government official in Egypt. As the administrator of several districts, his fame rested on the irrigation canal that he constructed over six years, bringing water to a parched agricultural landscape. So successful was he that he was given the Arabic title Sani al-Dawla (‘The Noble of the State’).

Many great Jewish thinkers, scholars and poets lived in Muslim lands. Maimonides – Musa ibn Maymun in Arabic, Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon in Hebrew and known by his Hebrew acronym as the Rambam – was the greatest Jewish scholar of the Middle Ages. In 1164, having fled Muslim persecution in Fez, he settled in Egypt under the tolerant Shi’ite Fatimids, where he became a court physician. In his writings on food and diet he advocated a ‘shared convivial meal’ as a way to conquer anxiety and tension ‘and also suspicion between ethnic groups’.

Close to power in Islamic society, Maimonides spoke and wrote in Arabic and was conversant with Arab thought and culture. In Cairo, one of the great intellectual centres of the Arab world, he entered an environment that encouraged his learning and his creativity. He also served as Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community there. His fame as a physician was such that Saladin, when Sultan of Egypt, appointed him court physician.

Among Maimonides’ medical writings was Fi ‘l-Jima’a (‘On Sexual Intercourse’), a treatise on sex and aphrodisiacs concentrating heavily on dietetics, a branch of medicine in which he was a pioneer. The treatise was commissioned by Sultan Omar, the nephew of Saladin. Intended for a non-Jewish reader, it was distributed in Arabic.

A draft proclamation survives declaring Maimonides Ra’is al-Yahud, ‘Head of the Jews’, recognised by the Muslim authorities as the official representative of the Jewish community in Cairo.

The great Muslim warrior, Saladin, a Kurd and scourge of the Christian Crusaders, conquered Jerusalem in 1187 after a five-month siege. Saladin encouraged the Jews to return to the city. Some came from as far south as Yemen, others from North Africa. Between 1209 and 1211, Jews also reached Jerusalem from England, northern France and Provence. Some 300 rabbis in all were welcomed to the city by its Muslim rulers.

There are many other examples of constructive cross-cultural engagement. Accounts survive of the revenue and expenditure of a large house in Cairo lived in by Jews and Muslims in 1234 and owned jointly by them. There were no doubt other such arrangements. Like Maimonides, many Jews attained well-remunerated positions as doctors at Muslim courts, under almost all but the most fanatical caliphates, often holding considerable influence. Jewish doctors for whom medicine had long been a traditional speciality were highly prized in Muslim societies. So too were Jewish linguists, writers and poets.

In the city of Basra, wrote an Italian Jewish traveller, Jacob d’Ancona in 1270,

‘there are not only traders among the Jews, but also tailors, workers in wood, leather and iron, makers of shoes and saddles as well as many apothecaries and physicians, from the great skill and knowledge of the Jews in the healing of men and from the understanding of their nature’.

Starting in the 14th century, the Ottoman Turks created a vast Muslim empire, in which Jews were an accepted and integral part of the fabric of society. Jewish merchants were the principal tradesmen in Baghdad. In Tunis and Algiers, Jews served as the conduit for Ottoman trade with Christian countries across the Mediterranean.

Among the Jews who came to the Ottoman city of Edirne (in western Turkey) from Christian Europe was Rabbi Isaac Tzarfati, who was made Chief Rabbi of the Ottoman dominions in the 14th century. In a letter to the Jews of Germany, France and Hungary, he wrote to the Jews of Europe [about Ottoman Turkey] to ‘inform you about how agreeable is this country’.

Here I found rest and happiness; Turkey can also become for you the land of peace … Here the Jew is not compelled to wear a yellow hat as a badge of shame, as is the case in Germany, where even great wealth and fortune are a curse for a Jew because he therewith arouses jealousy among Christians … Arise my brethren, gird up your loins, collect your forces, and come to us. Here you will be free of your enemies, here you will find rest …

Self-government

From the first days of his conquest of Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1453, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II encouraged Jews to settle in the city and to govern themselves in their own religious-based community. Property was offered free to Jewish newcomers, with a substantial exemption in their taxes for an extended period and with permission to build synagogues – thus ignoring an age-old Muslim prohibition for dhimmis to build any new places of worship. By 1478 there were 1,647 Jewish households in Constantinople – 10,000 people – constituting 10 per cent of the total population.

Jews continued to fight as companions-in-arms with Muslim soldiers against the Christians. In 1431 they were an integral part of the army of Sultan Muhammad IX of Granada at the Battle of Higueruela, where, unfortunately for both Jews and Muslims, Muhammad IX’s forces were defeated by the army of King John II of Castile.

The expulsion of the Jews from Christian Spain in 1492 saw at least 130,000 move to Muslim lands. Joseph Hamon, who had fled from Spain, became court physician to two Ottoman sultans, Bayazid II and Selim I. His son Moses succeeded him as court physician and looked after the health of Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520-66), whom he accompanied on his military expedition against Persia. Moses Hamon wrote several books on medicine, including an important one on dentistry, which is today in the Istanbul University Library.

Under the rule of Suleiman the Magnificent, Jews gained important positions in court. A document in the Topkapi Palace archive, dated 1527, mentions among the silversmiths in his service, ‘Abraham the Jew’, who specialised in laying gold and silver leaves under the sultan’s precious stones in order to accentuate their brilliance.

When Abbas I became Shah of Persia in 1588 Jews were at first much favoured. During his military campaign against the Georgians in the Caucasus, Jewish soldiers fought in Abbas’s army. In appreciation of their help, he allowed them to establish a new Jewish community, Farahabad – ‘City of Joy’ – on the shore of the Caspian Sea. When Abbas moved his capital from Kazvan to Isfahan many Jews went to live there.

Each succeeding century saw Jews living in Muslim lands discover opportunity and contentment, while at the same time being subjected to outbursts of fanaticism, attack and even massacre. No Muslim country was free from periods of anti-Jewish sentiment, or devoid of times of conciliation and peaceful coexistence.

Jews flourished in Egypt and Iraq, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s. But with the advent of Zionism and Britain’s promise of a Jewish national home in Palestine, growing Arab nationalism – which Britain had also encouraged – began to champion the Palestinian cause and to demand an end to Jewish immigration into Palestine. At the same time, Islamic fundamentalism, inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, denounced all Jewish immigration to Palestine, even to those areas where Jews had been farming for many decades. They began to portray Jews in Muslim lands – few of whom were Zionists – as disloyal and alien.

Israel and Palestine

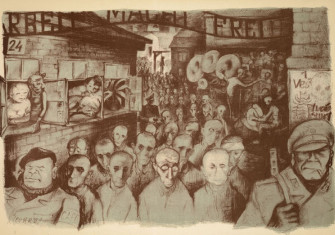

As anti-Zionist feeling intensified in the 1930s, inflamed by Nazi and Fascist radio propaganda and German emissaries, so the Jews living in Arab lands, their home throughout 1,400 years of Muslim rule, felt increasingly insecure.

Starting with the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, more than half a million Jews fled or were driven out of the lands in which they had lived for so long with their Muslim neighbours. Their plight mirrored that of the more than half a million Palestinian Arab refugees fleeing or driven out of Israel.

Today, the large Jewish communities that existed a century ago in more than 15 Muslim nations are no more. When British troops entered the Iraqi port of Basra in 2003, at the beginning of the Second Gulf War, a single Jew lived there, 80-year-old Selima Nissin. She was found by a Scottish lieutenant. Fewer than a dozen Jews were living elsewhere in Iraq in 2003; in 1948 there had been more than 150,000. In 2005 the BBC reported that only one Jew remained in Afghanistan. His name was Zebulon Simantov, the last of an ancient Jewish community of many thousands. Only in Morocco has the monarch, King Muhammad VI, acted like the Ottoman sultans in earlier centuries, encouraging his country’s 2,000 Jews; 80 years ago there had been more than a quarter of a million.

Will the 50,000 Jews who still live in Muslim lands, including the 25,000 in Iran, be able to achieve a security and a secure Jewish life that in so many ways was denied them in the past? There are good and bad precedents.

The history of the Jews living in Arab and Muslim lands has been a varied and remarkable one. Times of suffering and danger have alternated with times of achievement and fulfilment. Jews have been respected, admired and emulated; they have also been persecuted, robbed and killed. But they stayed and welcomed the times of good relations with their Muslim neighbours.

For 1,400 years Jews, in their different ways, made enormous contributions to the wellbeing and continuity of the umma – the worldwide community of Muslims. They had no subversive intentions and no desire to convert Muslims to Judaism, or in any way to subvert the Muslim religion.

A future from the past

The exodus and dispersal of the Jews in Arab and Muslim lands after 1948 was an irreversible interruption to a 1,400-year story of remarkable perseverance, considerable achievements and justifiable pride. For that reason, I dedicated my most recent study of Jewish populations in Muslim lands ‘to the 14 million Jews and the 1,400 million Muslims in the world in the hope that they may renew in the 21st century the mutual tolerance, respect and partnership that marked many periods in their history’. This could be the aim of all Jews and Muslims and their friends on both sides of the existing divide, who want a peaceful, productive, fulfilling relationship in the remaining nine decades of the 21st century. It is my hope that, in some way, my work will encourage a better understanding of history and with it a future that emulates only the best of the past; and there is much of that.

Each month, despite the ongoing strife, sees new signs of hope. In June 2010, for example, the Premier of the Canadian province of Ontario, Dalton McGinty, was among the visitors to the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, located in Israel’s Arava Valley, a place where Muslim and Jewish students – from Israel, the Palestinian West Bank and Jordan – work together on complex environmental issues, the solutions to which are crucial to the region’s future prosperity and stability. Similar joint projects abound, in education, science, medicine and the arts. Each one is a beacon of light and a potential harbinger of harmony.

Sir Martin Gilbert (1936-2015) was a historian of Winston Churchill, the 20th Century, and Jewish history. He was a member of the Chilcot Inquiry into Britain's role in the Iraq War. His last book was In Ishmael's House: A History of the Jews in Muslim Lands (2010).