Was Richard III a Bad King?

Child-murderer, arch villain, failed monarch, ‘northern’. Have efforts to redeem Richard III succeeded or is he still one of history’s worst kings?

‘Richard resolved to be a good king and even a reformer’

Michael Hicks, Professor Emeritus of History, University of Winchester and author of Richard III: The Self-Made King (Yale University Press, 2019)

For 500 years Richard III was a usurper and a wicked uncle, the murderer of his little nephews, the Princes in the Tower. He rightly suffered defeat and death at the Battle of Bosworth (1485). Strenuous efforts since the 1930s have sought to rehabilitate him as the victim of libellous Tudor propaganda. In 2015 his bones were royally reinterred within a splendid table-tomb at Leicester Cathedral.

Surely Richard was the least successful of English kings. His reign was brief (1483-85) and he left no legitimate issue and no political heirs. He destroyed his immediate Yorkist family and indeed the whole Plantagenet dynasty. He plunged England back into civil war. He re-started the Wars of the Roses that had ended with Yorkist victory in 1471; the conflict raged on for another 20 years. Richard’s principal achievement, albeit inadvertent, was to make feasible the vestigial claim of the obscure Henry Tudor and to create the Tudor monarchy. His regime was catastrophic.

That Richard failed was his own fault. His accession flouted accepted conventions, his title was not credible and many Englishmen doubted his justifications. Richard was also the commander defeated at Bosworth.

Yet Richard resolved to be a good king and even a reformer. He distanced himself from the immorality of Edward IV’s court and the forced loans that Edward had exacted. Repeatedly he declared his adherence to his coronation oaths. He promised justice to all. He was a capable administrator, more hardworking and consistent than Edward IV.

Richard started his reforms immediately on all fronts. He established the College of Arms, the Council of the North, and mastership of Requests. He reorganised royal estate management and founded two new chantry colleges. Yet none of his initiatives endured. Richard’s reign was too brief. He had to focus on defence against his foes; later, Henry VII, maliciously, undid his work. Had Richard prevailed at Bosworth, his reputation might have been viewed as more positive, like those of Henry IV and Edward IV, both of whom polished off their predecessor. But Richard never recovered from his illicit usurpation. Not a bad king, Richard’s reign was nevertheless disastrous.

‘Richard’s contemporaries believed he was capable of anything’

Gordon McKelvie, Senior Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of Winchester and author of Bastard Feudalism, English Society and the Law: The Statutes of Livery, 1390-1520 (Boydell Press, 2020)

Richard III is perhaps the most maligned king in English history, but he is also the king for whom the greatest effort has been expended on rehabilitation. The image of the cruel child-murdering monster immortalised by Shakespeare is perhaps taken with a pinch of salt these days.

Judgements on Richard III inevitably centre around his responsibility for his nephews’ deaths. Gossip persisted throughout Richard’s reign about the princes and he never tried to correct such assumptions. Yet more can be said about Richard than just his treatment of his nephews.

Richard’s wife, Anne, died in March 1485. According to the Crowland Chronicler, Richard was forced to deny to his council that he had poisoned her to marry his niece, Elizabeth. This extraordinary event gives an insight into how people thought of Richard; he seems to have been truly heartbroken by his wife’s death, but his previous behaviour evidently meant that his contemporaries believed he was capable of anything.

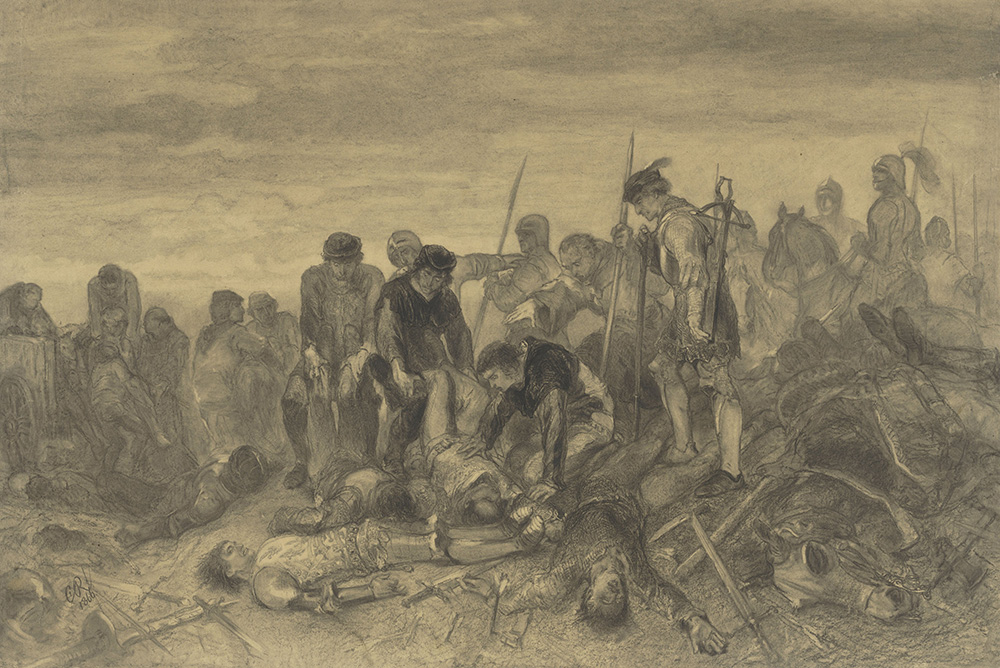

Ultimately, Richard failed as a king, losing his crown and his life at the Battle of Bosworth. How he died was unfortunate and speaks to his courage and bravery. Seeing Henry Tudor on the field, Richard charged, presumably in the hope of killing his enemy and ending the battle instantly. However, he was cut down and killed; a calculated gamble that, although risky, was rational.

The situation around the Battle of Bosworth, a conflict that most nobles avoided, demonstrates Richard’s failures. The Stanley family illustrate this better than anyone: sitting on the sidelines of the battle, only weighing in on behalf of Henry Tudor when it was clear he would win. Richard was sceptical of William Stanley and took his son George as a hostage to prevent Stanley support for Tudor. Even that was not enough to ensure their loyalty.

That many allies of his brother, Edward IV, supported Henry Tudor speaks to Richard’s inability to command widespread loyalty. Richard’s rule failed because too few people supported him, either from fear of becoming embroiled in continual civil war, or because they believed Richard was an individual capable of the most heinous of crimes.

‘Richard has one of the most lamentable tenures of England’s medieval monarchs’

Sarah Peverley, Professor of English Literature at the University of Liverpool and editor of John Hardyng Chronicle: Edited from British Library MS Lansdowne 204 (Medieval Institute Publications, 2015)

Considering the length of his reign and his accomplishments, Richard III has one of the most lamentable tenures of England’s medieval monarchs. His accession and removal of his nephews seeded unrest and reputational damage long before Tudor propaganda set out to vilify him. Yet categorising Richard’s reign in binary terms of good and bad sidesteps the nuances of context. Reflecting on the attitudes and actions that contributed to his rise and fall is a more productive way of approaching his reign.

Shaped by ambition and a vicious political landscape, Richard’s formative years taught him that power was built on property, affiliations, military action and the removal of opposition, as much as birth right. By 1483, he was unsurpassed in the north and poised to further his dominion in Scotland. Edward IV’s untimely demise redeployed this ambition, driving him to protect his status and pursue even greater influence, first as Lord Protector (as his brother and others seem to have desired) and then as king.

The tactics he used to respond to the real or imagined threat posed by the Woodvilles’ control of Edward V were no different from those employed by the men who raised him. In executing alleged traitors, launching targeted reputational attacks and seizing the monarch, Richard adopted the ‘kill or be killed’ attitude that allowed his brother to gain and retain the throne. The difference was that Richard had always been steadfastly loyal to Edward IV and in the eyes of his subjects the throne wasn’t his to take.

Richard’s subjects and foreign observers were stunned by his brazen betrayal, his swift execution of Lord Hastings, and the disappearance of his young nephews, all of which undermined efforts to stabilise the kingdom in the two years that followed. Further resentment and anxiety festered when Richard misjudged regional politics and redistributed southern property among his northern affinity.

Ultimately, the decisive but divisive actions that placed the crown on Richard’s head conjured the perfect storm of rumour and discontent that impoverished his reign and gave Henry Tudor a platform to challenge and end his rule.

‘Was Richard a bad king? His reign was too short to give a definitive answer’

Matthew Ward, Teaching Associate at the University of Nottingham and co-editor of Loyalty to the Monarchy in Late Medieval and Early Modern Britain, c.1400-1688 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020)

If longevity is one mark of a good king then Richard III falls short. Anyone losing their throne after two years would struggle to shrug off the label of ‘bad’ king. That said, 26 months was too short a time for a king to establish and consolidate his authority, particularly during the later 15th century.

Richard contributed to his own downfall in several respects. His reliance on northern supporters after the Duke of Buckingham’s rebellion was unpopular and concentrated power in too few hands. He had no choice: erstwhile supporters of Edward IV who Richard had retained in office joined the rebellion and they had to be replaced by loyal men. However, northerners were held with suspicion in the south. The Crowland Chronicle continuator described an invasion of northerners in the south under Richard’s rule; for some, Richard was seen as a ‘northern’ king.

Richard had issues with trust, for example placing too much confidence in the Duke of Buckingham. The king perhaps expected the same degree of faithfulness that he had shown his brother Edward IV, but Edward did not rate Buckingham and gave him no significant roles. Conversely, Richard demonstrated a distinct lack of trust at times, for example with William, Lord Hastings, summarily executed in June 1483.

Some of Richard’s actions were seen positively. He introduced legislation that regulated trade and reformed the bail system. He signalled an intention to uphold justice across the realm and protected those from the lower orders of society from exploitation by corrupt officials. He banned the unpopular ‘benevolences’ used by Edward IV to extract money. In 1525 Cardinal Wolsey asked London for a gift of money for Henry VIII but was reminded by a citizen that Richard III had outlawed them, adding that good laws were made during his reign.

Was Richard a bad king? His reign was too short to give a definitive answer. If his fateful charge at Bosworth had succeeded he could have reigned for many more years, during which he would have had the chance to shape his own legacy.