The Prophecies of Merlin

As told by one medieval chronicler, Britain’s past and future had been prophesied by Merlin, who foresaw its rise, fall and conquest. Did the magician have warnings for the present?

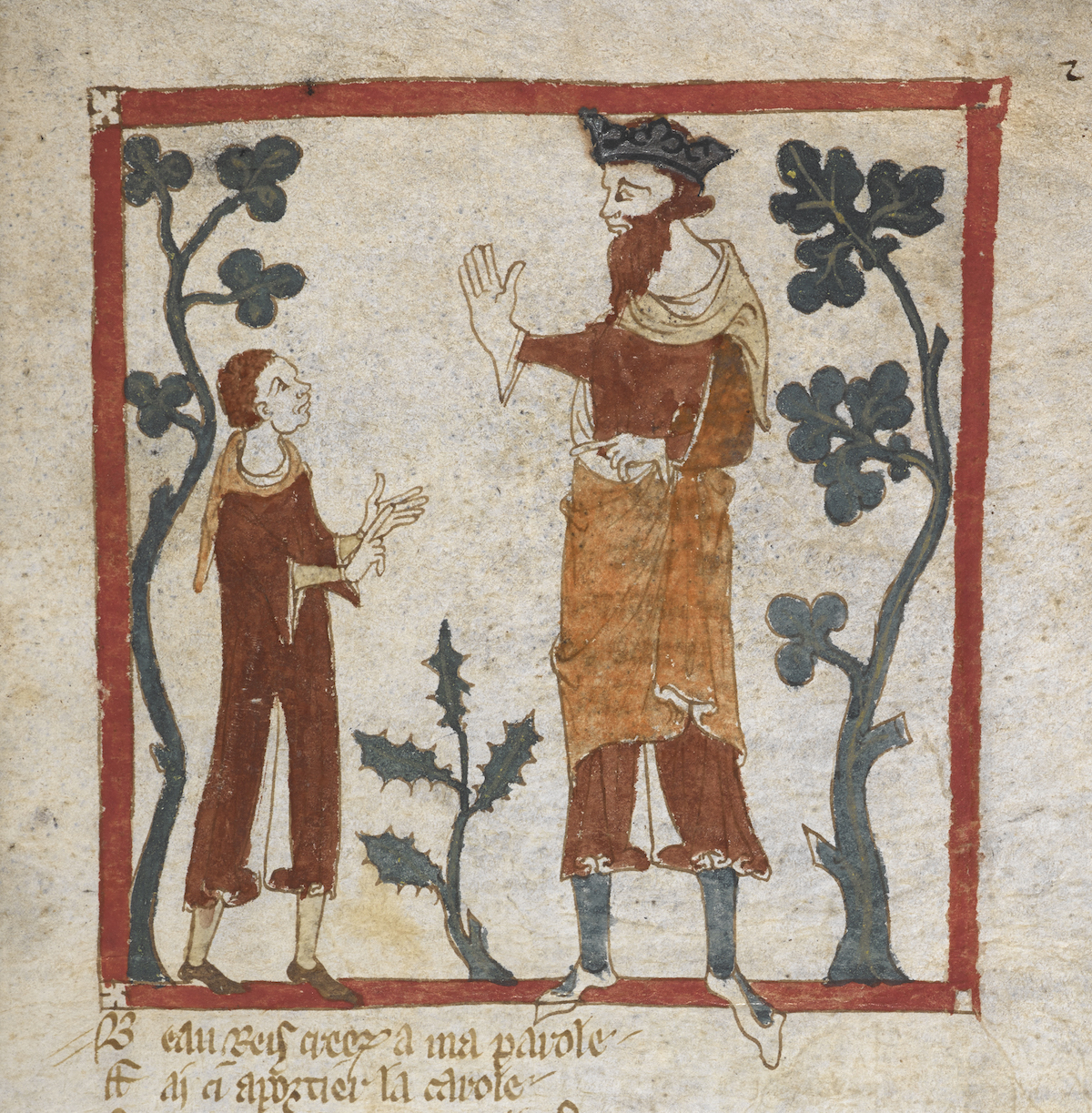

Prophecy is an inherent and integral part of medieval history; any book of history written in Western Europe during that period will almost certainly include some sort of prophetic content. The Bible, together with various pagan traditions of prophecy, provided the main sources of inspiration. However, a new prophetic discourse emerged in England during the 1130s: political prophecy, first successfully employed in the Prophecies of Merlin (1135), written by the Oxford-based cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Merlin’s ‘prophecies’ were not the first to have political implications. Prophecies found in the Bible – as in Numbers, Isaiah and Ezekiel – could seem political since they often pertained to despotic rulers and the fate of nations. What distinguished this new political prophecy was that political figures, particularly kings, and events (as opposed to spiritual matters) were the primary subjects. Often told through animal allegories, they could be repurposed for successive generations.