A History of the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910, was one of the great revolutionary upheavals of the 20th century. What were its causes and consequences?

Perhaps because it remained distinctively national and self-contained, claiming no universal validity and making no attempt to export its doctrines, the Mexican Revolution has remained globally anonymous compared with, say, the Russian, Chinese and Cuban revolutions. Yet, on any Richter scale of social seismology, the Cuban Revolution was a small affair compared with its Mexican counterpart. Both absolutely and relatively, more fought in Mexico, more died, more were affected by the fighting, and more was destroyed. Yet (in contrast to Cuba) the outcome was highly ambivalent: scholars still debate (often in rather sterile fashion) whether the Mexican Revolution was directed against a ‘feudal’ or ‘bourgeois’ regime, how the character of the revolutionary regime should be qualified, and thus whether (in terms of its outcome) the ‘revolution’ was a ‘real’ revolution at all, worthy of rank among Crane Brinton’s ‘Great Revolutions’.

But, irrespective of its outcome (and I would argue it wrought many, if not always obvious, changes in Mexican society) the revolution had one classic feature of the ‘Great Revolutions’: the mobilisation of large numbers of people who had hitherto remained on the margin of politics. ‘Revolution’, as Huntington writes, ‘is the extreme case of the explosion of political participation.’ As in the English Civil War, for a few years the world was turned upside down: the old elite was ousted, popular and plebeian leaders rose to the top, and new, radical ideas circulated in an atmosphere of unprecedented freedom. If, as in the English Civil War, this period gave way to counter-revolution, to the crushing or co-option of popular movements, and to the creation of new structures of power and authority, this did not represent a return to square one: the popular movement in Mexico (as in England) might meet defeat, but in defeat it profoundly affected Mexican society and its subsequent evolution; the ‘world turned upside down’ was not the same world once it had been righted again.

The Mexican Revolution began as a movement of middle-class protest against the long-standing dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz (1876-1911). Like many of Mexico’s 19th-century rulers, Diaz was an army officer who had come to power by a coup. Unlike his predecessors, however, he established a stable political system, in which the formally representative Constitution of 1857 was bypassed, local political bosses (caciques) controlled elections, political opposition, and public order, while a handful of powerful families and their clients monopolised economic and political power in the provinces.

The whole system was fuelled and lubricated by the new money pumped into the economy by rising foreign trade and investment: railways spanned the country, mines and export crops flourished, the cities acquired paved streets, electric light, trams and drains. These developments were apparent in other, major Latin American countries at the time. But in Mexico they had a particular impact, and a unique, revolutionary outcome, The oligarchy benefited from its liaison with foreign capital: Luis Terrazas, a butcher’s son, rose to dominate the northern state of Chihuahua, acquiring huge cattle estates, mines and industrial interests, and running the politics of the state to his own satisfaction; the sugar planters of the warm, lush state of Morelos, near the capital, imported new machinery, hoisted production, and began to compete on world markets (they could also holiday at Biarritz and buy foreign luxury goods – whether French porcelain or English fox-terriers); Olegario Mohna ran the economy and politics of Yucatan, where his son-in-law handled the export of henequen, an agave plant amd the state's basic crop, and, among his many lesser relatives and clients, a second cousin was Inspector of Mayan Ruins (he had never visited Chichen Itza, he told two English travellers, but ‘had satisfactory photographs’).

Money also bolstered the national government. The perennially precarious budget was stabilised in the 1890s and Mexico’s credit rating was the envy of Latin America. In 1910, when the ageing dictator played host to the world’s representatives on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of Mexico’s independence, peace and prosperity seemed assured.

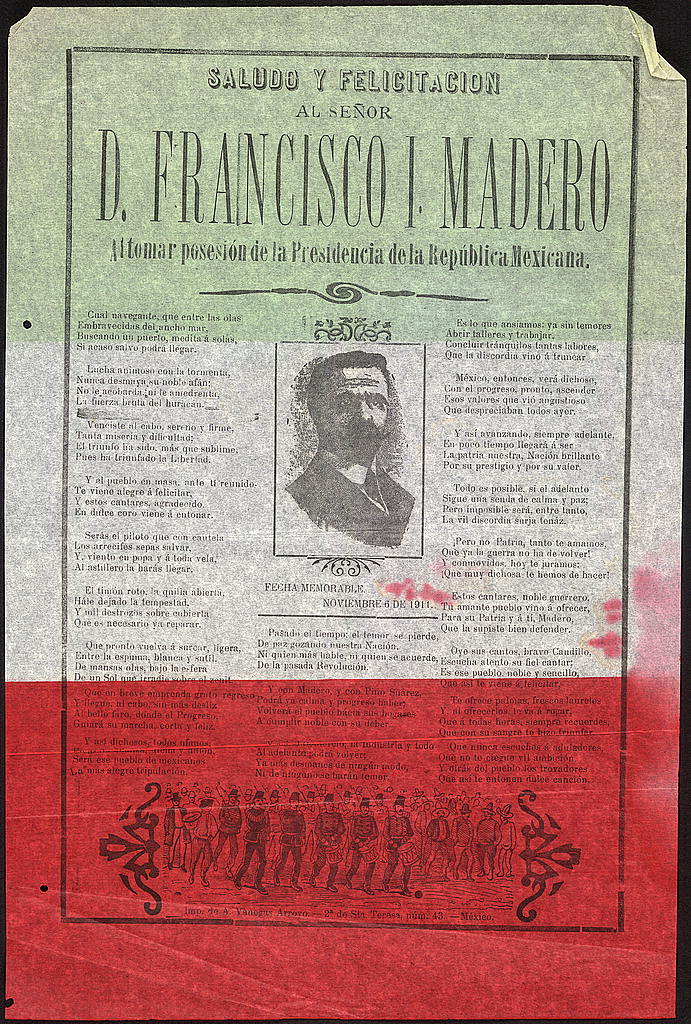

They harked back to the liberal heroes of Mexico’s past, and made comparisons with the flourishing liberal democracies of Europe and North America. Finally, they feared for Mexico’s (and their own) future if Diaz died politically intestate, without bequeathing to the nation a form of viable, representative government. Accordingly, they readily responded to the appeal of Francisco Madero, a rich northern landowner and businessman who – more out of idealism than naked self-interest – began to campaign for a stricter implementation of the 1857 Constitution, which was still chiefly honoured in the breach. ‘Sufragio Efectivo, No Re-eleccion’ (A Real Vote and No Boss Rule) was the slogan of Madero and his Anti-re-electionist Party, and their political campaigns of 1909-10 were characterised by vigorous journalism, mass meetings and whistle-stop tours all the paraphernalia of the North American democracy which they sought to emulate. Initially complacent, Diaz was rattled by the mounting political agitation. On the eve of the 1910 presidential election (in which Madero opposed Diaz: most of the family agreed with grandfather Evaristo Madero’s dismissive comment that this resembled ‘a microbe’s challenge to an elephant’) Madero and his close allies were gaoled, and the election was conducted according to the usual principles of corruption and coercion. Diaz won.

Madero was expected to take note and return, suitably chastened, to his northern estates. Most of his followers educated, middle-aged, frock-coated liberals did return to their classrooms, companies and law firms. They could make good speeches and pen elegant articles, but more was beyond them. An armed revolt? ‘It was dangerous,’ they agreed when they discussed the matter in Yucatan. ‘Nobody was partisan of shedding blood and, even if everybody had been so, there was no money, time, nor people expert in a movement of that sort.’ So thought most Maderistas. Not so Madero. Small, quirky, mild-mannered, and something of a political naif, Madero had a generous belief in the good sense and reason of the people (just as he believed in spiritualism and the virtues of homoeopathic medicine). Rather than capitulate to Diaz, Madero called upon the Mexican people to rise in arms on November 20th, 1910.

***

The appeal enjoyed sudden, surprising success because it struck a chord with a second group, the illiterate rural mass, the Indians and mestizos (half-castes) of village and hacienda, who formed the bulk of Mexico’s population, who provided the labour upon which the economy rested, but who lived, impotent and often ignored, on the margin of political life. It was not that they – like Madero and the city liberals – were enamoured of liberal abstractions and foreign examples: for them, ‘A Real Vote and No Boss Rule’ had a more concrete, particular and compelling significance. Under Diaz, the economy and the state had grown apace; but these processes, as is often the case, had had divergent effects, and the countryside, particularly the rural poor, had carried the burden of Diaz’s programme of modernisation. While the cities prospered, the great estates swelled to meet world and Mexican demand for primary products (sugar, cotton, coffee, henequen, tropical fruits), absorbing the lands of villages and smallholders, converting once independent peasants into landless labourers, who often worked under harsh overseers. As the old cornfields gave way to new cash crops, so food became more scarce and prices rose, outstripping wages. In some parts of Mexico a form of virtual slavery developed; and, in years of poor harvests, like 1908-09, the rural poor faced real destitution. With the monopolisation of land in the hands of landlords and caciques went a corresponding monopolisation of political power, and proud, often ancient communities found themselves languishing under the arbitrary rule of Diaz’s political bosses, facing increased control, regimentation and taxation.

In Morelos, entire villages vanished beneath a blanket of sugar-cane. In Sonora, in the north-west, the Federal army fought a series of bitter campaigns to dispossess the Yaqui Indians of their ancestral lands. Smallholders like the Cedillo family of Palomas, in the state of San Luis, battled against hacienda encroachments on their land. Villages petitioned (usually in vain) against the rule of caciques like Luz Comaduran of Bachiaiva, in the Chihuahua highlands, where municipal land had been expropriated by the cacique and his clients, where four thugs were employed to silence opposition, and where Comaduran’s period in office comprised ‘years of noose and knife ... involving the abuse of all laws, both municipal and civil, human and divine’. For such people, Madero’s revolution held out the prospect, less of a progressive liberal polity, inspired by Gladstone or Gambetta, than of the recovery of local freedoms, the reconquest of village lands, the overthrow of tyrannical bosses and landlords. Their vision was nostalgic, particular and powerful: they sought to recover the world they had lost, or were fast losing.

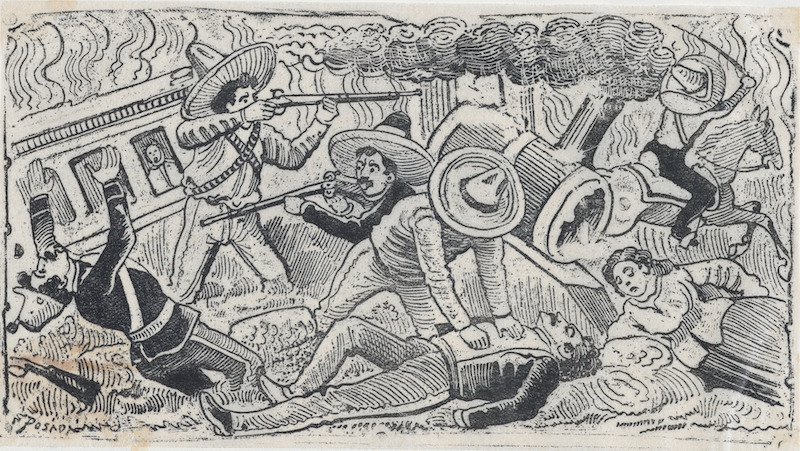

To general surprise, and to the government’s consternation, local armed bands sprang up during the winter of 1910-11, first in northern then central Mexico. Diaz’s rusty military apparatus proved unable to contain the spread of guerrilla warfare and, in May, 1911, his advisers prevailed upon him to resign, in the hope – well-founded as it turned out – that they could salvage something before the revolution proceeded too far. Six months later Madero was inaugurated president, following the freest election ever held in the country’s history.

***

The subsequent years were violent and chaotic. Madero’s liberal experiment failed. Adherents of the old regime – landowners, the military, top businessmen and clerics -blocked his modest reforms; and the latter came too slowly to satisfy the popular elements which had brought Madero to power in the first place. Caught in this crossfire, Madero was finally overthrown by the army and assassinated early in 1913; but the establishment of a draconian military regime under General Victoriano Huerta, a regime dedicated to ‘peace, cost what it may’ and to the substantial restoration of the old regime, only guaranteed the galloping inflation of popular rebellion. The people fought on, and the militarist solution, attempted to the limit in 1913-14, proved as naive and impractical as the liberal solution had in 1911-12. Meantime, during eighteen months of fierce fighting, which culminated in the fall of Huerta, the fabric of the old order was irretrievably rent: the Porfirian army, the local bosses, the state oligarchies, the church and the bureaucracy were forced to surrender much or all of their power.

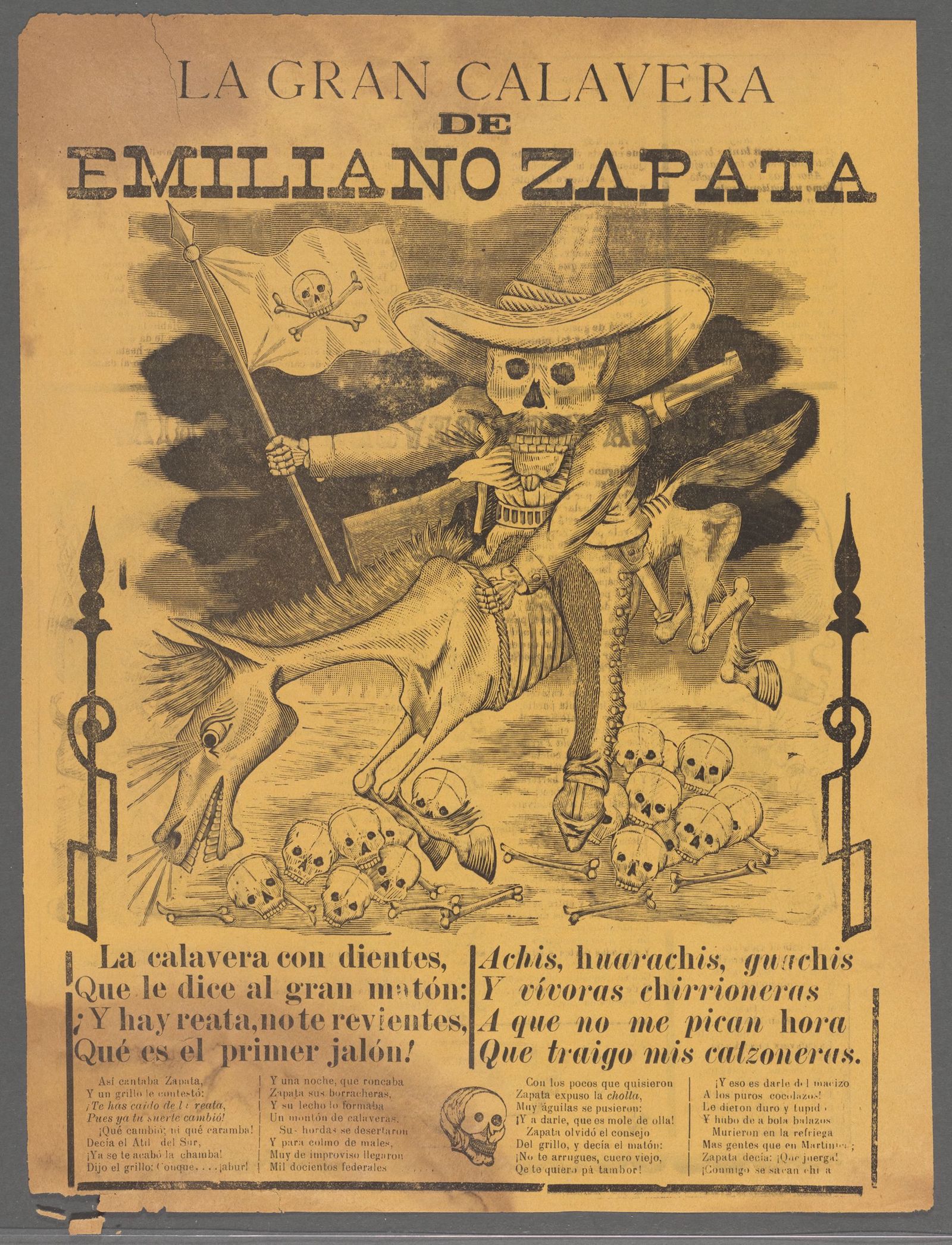

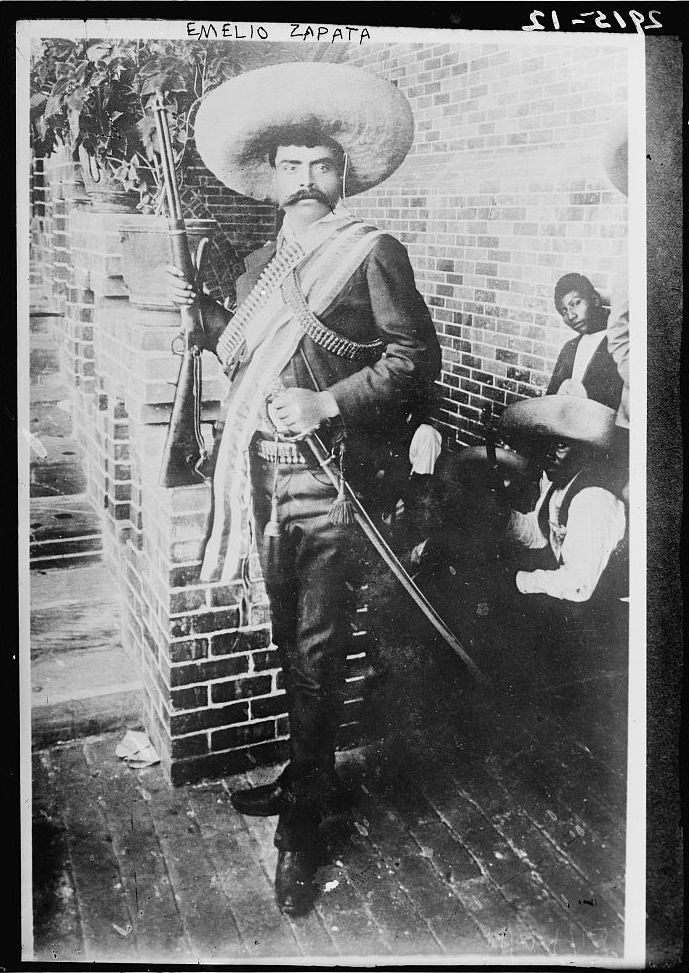

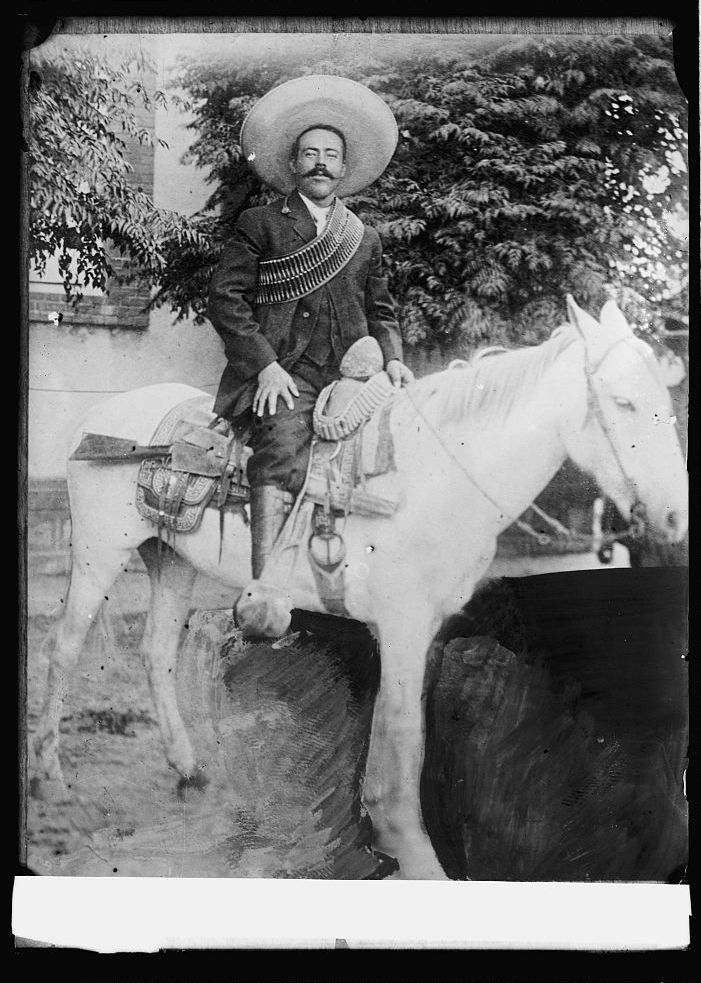

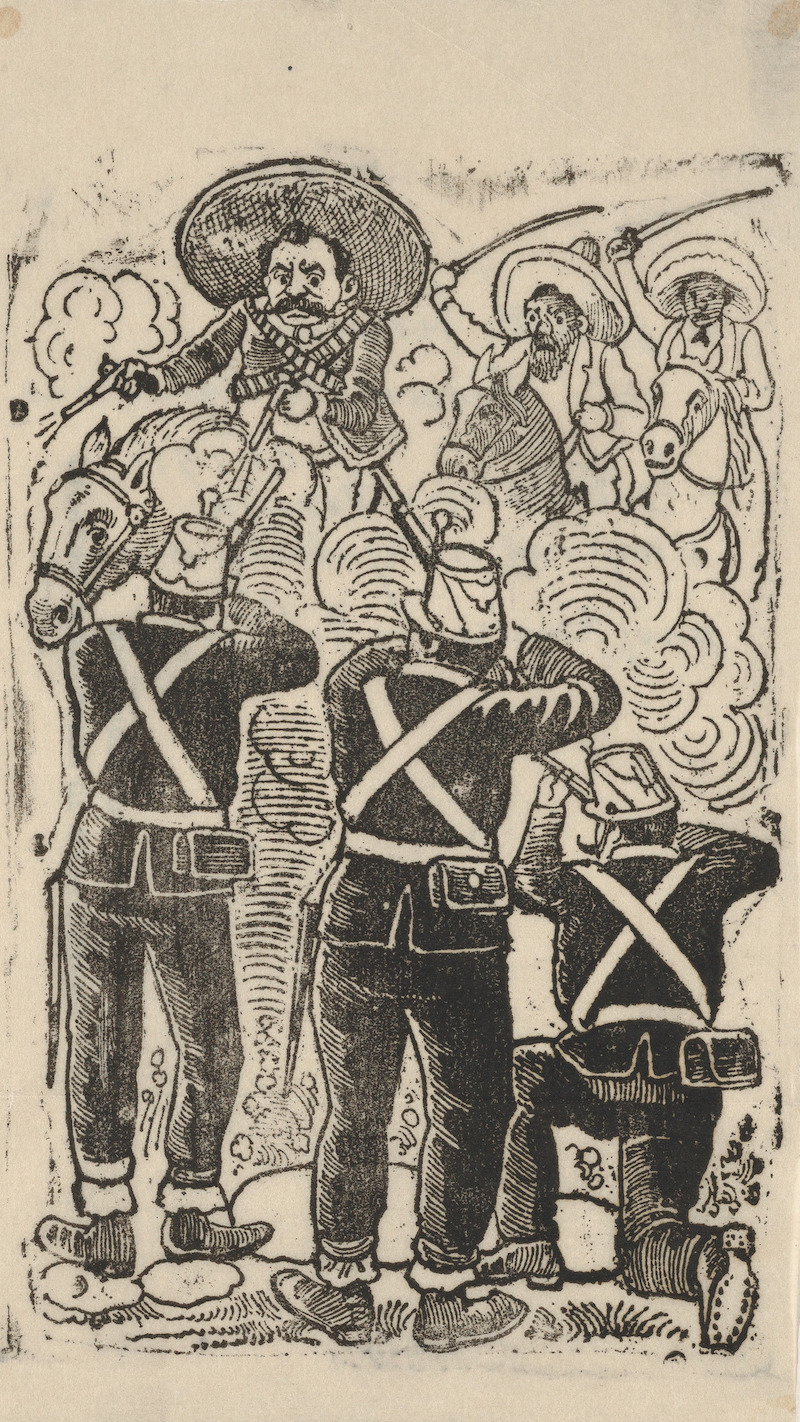

Who ruled Mexico in their place? For a time, in many localities, power had shifted into the hands of popular leaders, the bushwhackers and guerrilleros who had fought first Diaz, then Huerta. The two most famous and powerful were Emiliano Zapata and Francisco (‘Pancho’) Villa, who typified, in many respects, the main characteristics of the popular movement. Zapata led the villagers of Morelos in a crusade to recover the lands lost to the sugar estates, and from this objective he never swerved. Though city intellectuals later tagged along, writing his official communications and mouthing a bastard socialism, Zapata himself remained a man of the people, indifferent to formal ideologies, content with a traditional Catholicism, fiercely loyal to his Morelos followers, as they were to him. City politicians who attempted a dialogue with Zapata found him (like many of his kind) intractable: he was too cerrado, too closed – uncommunicative, dour, suspicious and alien to compromise. At home, in rural Morelos, Zapata cut the figure of a charro , a horse-loving, dashing, somewhat dandified countryman, who affected huge sombreros, tight silver-buttoned trousers, and shirts and scarves of pastel shades; a man who preferred to spend his time at cockfights, breaking horses, sipping beer in the plaza or fathering children. Underpinned by the mutual trust of leader and led, Zapata’s forces – despite their inadequate arms – dominated the state of Morelos for years, repeatedly confounding superior conventional armies. But, though Zapata forged alliances with neighbouring rebels, his horizons remained limited. When his troops occupied Mexico City late in 1914, Zapata slunk off to a seedy hotel near the station. Unlike Marlon Brando’s Zapata – in the Kazan classic, Viva Zapata! – he never occupied the presidential chair; indeed, he never much wanted to. Its deep local roots provided both the strength and weakness of the Zapatista movement.

It was just outside Mexico City, late in 1914, that Zapata and Villa, the great rebel chiefs of south and north, met for the first time: Zapata, slim, dark and dandified; Villa, ‘tall, robust, weighing about 180 pounds, with a complexion almost as florid as a German, wearing an English [pith] helmet, a heavy brown sweater, khaki leggings and heavy riding shoes’. Neither was very communicative: they eyed each other coyly ‘like two country sweethearts’; and, when Zapata, who liked his drink, ordered cognac, Villa, who did not take hard liquor, drank only to oblige, choked, and called for water. But they soon found out that they shared a common viewpoint, as they began running down the nominal leader of their revolution, the staid, elderly, ponderous and somewhat pedantic Venustiano Carranza.

Though their appearances were in marked contrast, and though their respective armies differed in important respects – Villa’s, recruited from the villages and cattlespreads of the north, was a more professional, mobile force, which had destroyed Huerta’s Federal army in its dramatic descent on the capital – nevertheless, the two caudillos shared a common popular origin and popular appeal. Villa, a peasant’s son driven to banditry, had become a devoted follower of Madero, and now robbed the rich and righted wrongs on a grand scale. He had no clear-cut agrarian cause, like Zapata; and his political grasp was no keener. But he had a knack for guerrilla fighting, and carried over his verve and charisma into the conventional campaigns of 1914, when the massed charges of the Villista cavalry shattered the Federals. With north and central Mexico in his palm, Villa ran unpopular landlords and bosses out of the country (the Terrazas clan were his chief victims) and distributed their property in careless fashion to friends and followers. He handed out free food to the poor and (his supporters said) established free education. During its brief existence, Villa’s regime bore the hallmark of one of Professor Hobsbawm’s ‘social bandits’.

Though his army grew and acquired many of the accoutrements of modern war – artillery, a hospital train, an efficient commissary – Villa, like Zapata, never lost touch with the common people who, in good times and bad, lent him their support. He still preferred popular pastimes – impromptu bullfights and all-night dances, after which Villa would arrive at the front ‘with bloodshot eyes and an air of extreme lassitude’. Though he avoided hard liquor (this, like his rheumatism, was a legacy of his bandit days) he womanised freely. And, though a general, he mixed readily with the rank and file, swapping jokes on the long, disorganised railway journeys which took his army and their camp-followers, like some huge folk migration, from the northern border down to Mexico City, Villa himself travelling in ‘a red caboose with chintz curtains and... photographs of showy ladies in theatrical poses tacked on the walls’. In battle Villa was always in the thick, urging on his men, rather than directing strategy from the rear.

If Villa and Zapata were the most powerful and famous revolutionary caudillos, there were many of similar type but lesser rank: indeed, the large rebel armies, like Villa’s Division of the North, were conglomerates, formed of many units, each with an individual jefe (chief), and usually deriving from a common place of origin. Some were men of the mountains, backwoodsmen resentful of the growing power of officials, tax-collectors and recruiting sergeants; some were villagers from the valleys and lowlands, victims of agrarian dispossession. The Laguna district, a cotton- and rubber-producing region near Torreon in north-central Mexico, provided several such bands, most of whom affiliated to Villa’s army for the major campaigns, while retaining a distinct, local identity. They were a rough crowd: an American missionary recalled how 100 of them wandered into his mission social in the summer of 1911 (they had just taken Torreon amid scenes of riot and pillage): they were ‘all of them big rough fellows yet with piercing eyes and a determined set of the head... they stayed more than an hour, sitting with gun in hand while they ate ice-cream’. A notorious trouble spot in the Laguna was Cuencame, an Indian village which had lost its lands to a voracious neighbouring hacienda in the 1900s. There had been protests, and the leaders were consigned to the army a preferred punishment of the Diaz government, and one which the common people particularly feared and disliked. Among them was Calixto Contreras, who after 1910 emerged as a prominent rebel chief. To a British estate manager, Contreras seemed Mongoloid and fearsome: ‘of sinister aspect and sidling looks’. A Mexican doctor, on Villa’s staff; who treated Contreras termed him ‘bald, dark and ugly’, and described how, on the door of Contreras’ railway car, hanging from an iron ring, was a 'stick bearing a blackened and repulsive head... tied with a red ribbon by cruel feminine hands to denote that it belonged to a colorado ’. But all, including the British estate manager, agreed that Don Calixto was genial and polite, a model of Mexican courtesy. His men, from Cuencame and the vicinity, were ‘simply peons who had risen in arms’ and the American journalist John Reed described them as ‘unpaid, ill-clad, undisciplined their officers merely the bravest among them armed only with aged Springfields and a handful of cartridges apiece’. Though they fought alongside Villa, their chief loyalty was to Contreras and Cuencame; hence to the more professional Villistas, like the brutal Rodolfo Fierro, they were ‘those simple fools of Contreras’. Yet for six years they combated diverse opponents, defending their patria chica – their little homeland – and ignoring the mirage of national power. Contreras rose to be a general, with the appropriate status and insignia (‘as much of a... misfit as any Napoleonic marshal’, he seemed); and when he was killed, in 1916, his son took his place.

Over the years, however, popular movements of this kind gradually lost their impetus. Defeated, or simply war-weary, the peon-soldiers returned to village and hacienda; the surviving leaders (who were few enough) reached deals or accommodations with the new ‘revolutionary’ government. So it was all over Mexico, as a semblance of peace was established late in the decade. By a strange irony, none of the original protagonists of the civil war achieved ultimate success: Diaz and Huerta, the champions of the old régime, failed to contain the forces of change and rebellion; but the rebels, too, both the pioneer city liberals and the popular forces of the country- side, proved unable (in the first case) and unwilling (in the second) to fasten their control on the country. A fourth power stepped into the vacuum: labelled the Constitutionalists, because of their supposed attachment to constitutional rule, they were in fact sharp opportunists, men of the northern states, particularly of the prosperous, Americanised state of Sonora. They were not grand hacendados or suave intellectuals; but neither were they rural hicks, tied to the ways of the village and the cycle of the agricultural year. They moved equally in city and countryside: if they farmed (as their greatest military champion, Alvaro Obregon, did) they were go-ahead, entrepreneurial farmers; or, like their greatest political fixer, Plutarco Elias Calles, they may have drifted from job to job school- teacher, hotelier, municipal official acquiring varied experience and an eye for the main chance. Though they lacked a classical education, they were literate, and often endowed with practical skills; and, though they had no deep roots in local communities (indeed, their very footloose mobility was one of their great assets in (he struggle for power) they saw and accepted – as neither Diaz nor Madero nor Huerta had done – that the post- revolutionary regime needed some kind of popular base. The masses who had fought in the revolution could not simply be repressed; they would have to be bought off too.

For the Constitutionalists, this was often a cynical process. The distribution of land to the villages was for them a political manoeuvre not – as with Zapata – an article of faith. It was a means to quieten and domesticate the troublesome rural population, turning them into loyal subjects of the revolutionary state. And the common touch which Constitutionalist generals like Obregon cultivated was – however skilled and effective – not quite the genuine rapport which Villa, Zapata, or Contreras had shared with their followers. But, artificial and self-seeking though Constitutionalist methods were, they worked. Where Madero had failed to hold national power, and neither Villa nor Zapata had seriously tried, the Constitutionalists were ready, willing and able. They were militarily able: in the final, decisive bout of civil war in 1915 Obregon comprehensively defeated Villa in a series of similar engagements. The massed charges of the Villista cavalry, successful against Huerta's reluctant conscripts, failed bloodily and ignominiously when the Division of the North confronted an army of mettle and organisation, and when Villa came up against a shrewd, scientific (albeit self-taught) general like Obregon, who had learned and applied the lessons of the Western Front.

Whipped, Villa retired to Chihuahua and reverted to semi-bandit status, raiding towns and villages with apparent impunity, still able to count on local support, and defying both the Mexican and the American forces sent to hunt him down. This was his natural habitat and metier. Zapata, too, continued his guerrilla war in Morelos until, in 1919, he met the usual fate of the popular champion and noble robber: invulnerable to direct attacks, he was lured into a trap and treacherously killed. Other popular leaders went the same way. Villa survived his old ally by four years. With a semblance of peace restored, and Obregon installed in the presidency, Villa was amnestied by his old conqueror and granted a large estate where he and his ageing veterans might live out their declining years. But Villa had many vengeful enemies; and the central government, notwithstanding its amnesty, feared a possible revival of the old caudillo in the north. In July, 1923 Villa was gunned down as he drove through the streets of Parral.

Most of his lieutenants had gone years before: Ortega, dead of typhoid after the battle of Zacatecas; Urbina, executed at Villa’s own orders for insubordination; Fierro, drowned in a quicksand during the Villista retreat of 1915. And what of those popular leaders who, against the odds, survived? A British estate manager who had met many of these northern revolutionaries observed:

One witnessed the truth of some adage that tells that leadership developed in the field unfits the former civilian for those constructive and administrative tasks which the violent episodes historically should be the prelude. Few of these leaders ultimately survived into what one may call the immediate post-insurrection period, the twilight of the dawn of peace; and other men strode across the graves of these turbulent and homespun but mostly well-meaning patriots to grasp the administrative powers that should have been their reward.

But it was not just a question of mortality, nor even of the transition from war to peace (for history surely affords enough examples of leaders emerging from the episodes of violence to assume the tasks of administration: Cromwell, Napoleon, Eisenhower – even Obregon himself, who proved as shrewd a businessman and president as he had been a general). Rather, it was a question of the kind of war and the kind of peace. The qualities which made Villa, Zapata, Contreras and others redoubtable revolutionaries and guerrilla fighters often disqualified them from subsequent political careers: they were too provincial, ill-educated, wedded to a traditional, rural way of life which, in many respects, was on the way out.

The future belonged to nationally-minded, citified operators: not Madero’s refined liberals, but the sharp, self-made men of Sonora, or at least men cast in their image – like Nicolas Zapata, son of the revolutionary, who acquired land, wealth and power in Morelos, having ‘earned the rudiments of politics – which rotted his sense of obligation’ to the local community. Nicolas Zapata was of the post-revolutionary generation: as a nine-year-old he had slept through his father’s famous meeting with Villa. Of the original generation of popular revolutionaries, some found a place in the new regime, not least because it was to the regime’s advantage, while a few assimilated successfully. Joaquin Amaro, for example, the son of a muleteer and a fine horseman, fought throughout the revolution as a young man, wearing in his ear a gold earring as a love token (or, some said, a red glass bead as a protective amulet); but he became a loyal ally of Obregon, discarded his earring (or bead), exchanged his mustang for a polo pony, and rose to be Minister of War – and a dynamic, efficient Minister of War too.

But such willing and successful transformations were rare. More often, popular leaders who survived the fighting only adapted imperfectly and with reluctance. The new world was not to their liking; it was certainly not what they and their followers had fought for. Saturnino Cedillo outlived his brothers – all of whom had perished in the fratricidal conflict – and became governor and state boss of San Luis. He did well by his old supporters, settling them on lands in the state, but he could not altogether fathom the ways of new, post-revolutionary regime. When Graham Greene met him in March, 1938 he seemed a lonely, embattled survivor of the good old days who, while retaining a happy, if paternalist, rapport with the local peasants, exuded ‘the pathos of the betwixt and between – of the uneducated man maintaining himself among the literate’. For Cedillo, the complexity of modern politics, the labour of administration and the conflict of rival ideologies were – in 1938, as twenty years before – to be shunned: ‘he hated the whole business; you could see he didn’t think in our terms at all... he had been happier at sunset, jolting over the stony fields in an old car, showing off his crops’. Within weeks, Cedillo had been goaded into rebellion by the central government, driven into the hills, hunted down with planes, and finally killed. The Cedillo ‘revolt’ (as the government chose to call it) was the last kick of the good old cause, final proof that the popular revolutionary movement had passed into history. It survives only in the myths, murals and revolutionary rhetoric of modern Mexico.